The northwest side of Mount Baldy as seen from the Lightning Ridge Nature Trail ( summit is between the two pines in foreground). To the left of Mt. Baldy is Pine Mountain. It too, still has some snow on its’ slopes. Mount Baldy, officially known as Mount San Antonio, is the highest peak in the San Gabriel mountains at 10,064′ elevation. That’s the Angeles Crest Highway (Hwy. 2) coming up from the mountain village of Wrightwood on the left side of photograph.

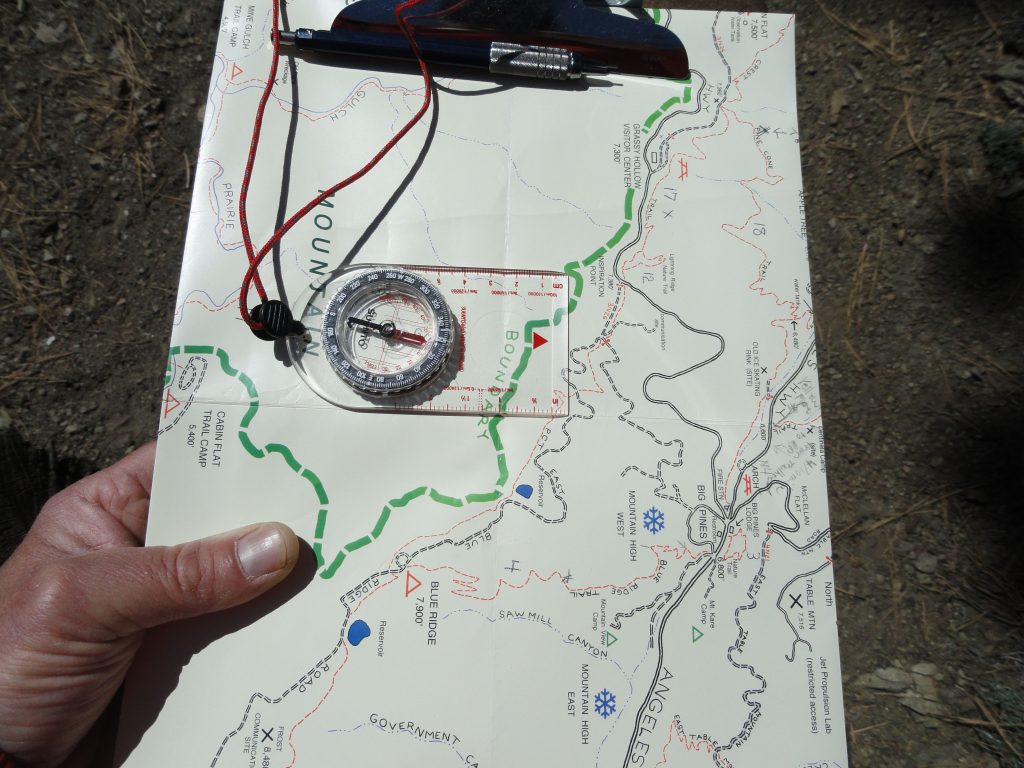

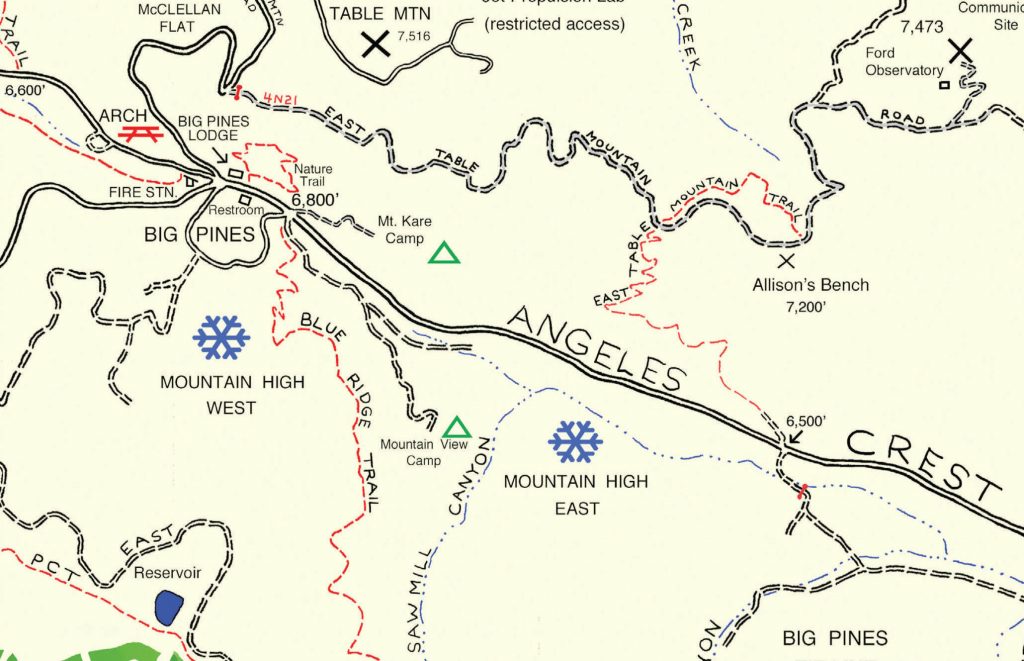

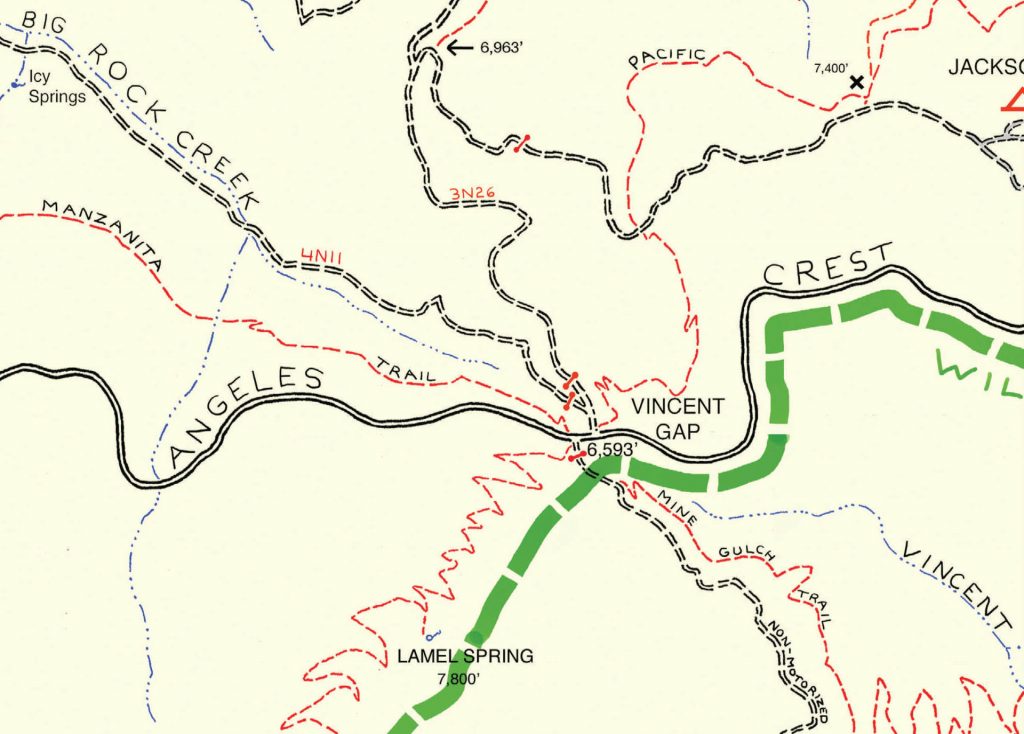

Now that it’s May and the days have started to warm up and lengthen, consider walking the Lightning Ridge Nature Trail. It’s up 7,300′ on the spine of the San Gabriel mountains. This is high country with fabulous views in all directions. A short drive west of Wrightwood, approximately 5 miles, takes you to the trailhead just across Hwy. 2 (Angeles Crest Highway) from Inspiration Point.

Colorful lichens make these wind swept boulders their home atop the San Gabriel mountains. Elevation is 7,400′ on an exposed ridge top. Lightning Ridge Nature Trail – Wrightwood, CA.

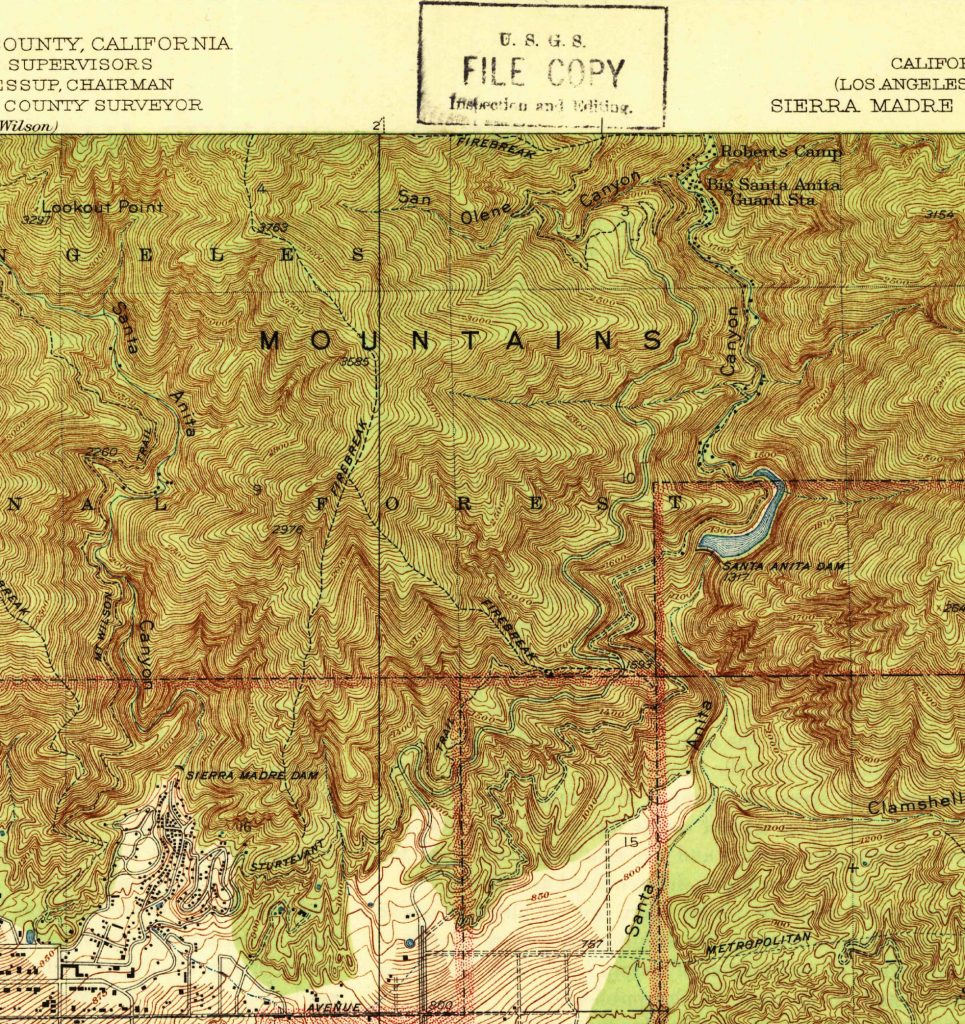

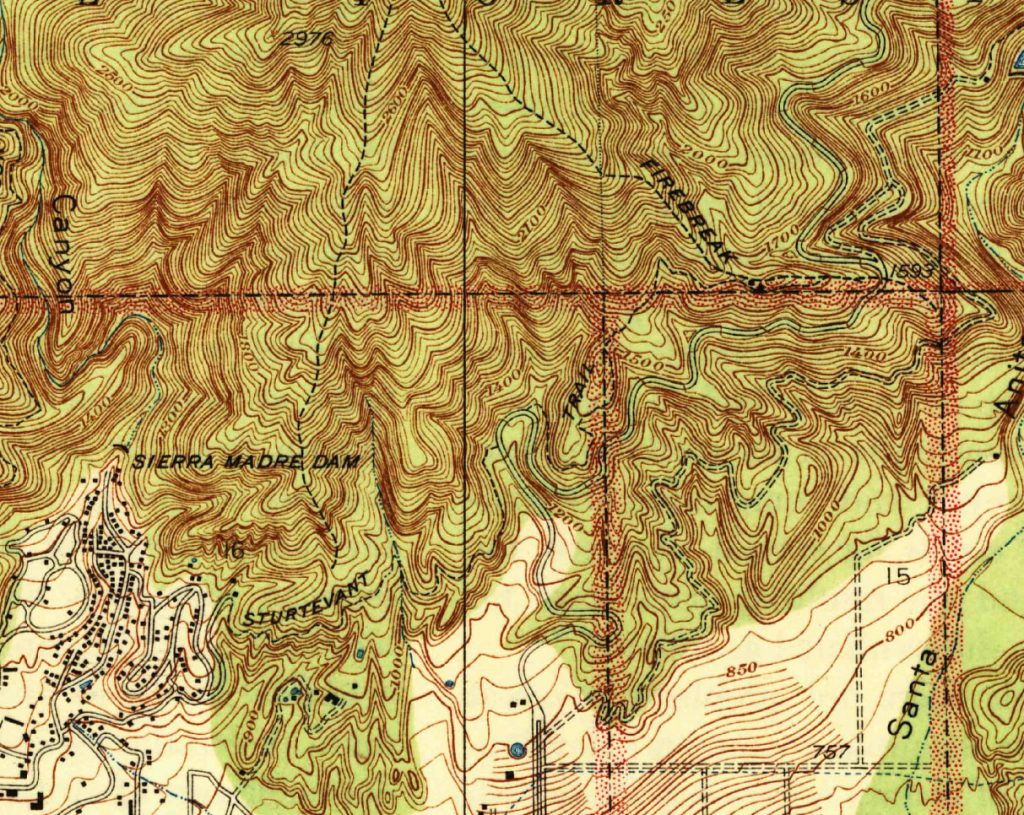

The trailhead is on the north side of Hwy. 2 in a wide turnout next to a backdrop of willows and shrubs. There’s a red metal picnic table there as well. Find your way through the little brushy opening and you’ll see a PCT (Pacific Crest Trail) signpost marking the trail to your left. You’ll take the trail directly in front of you, contouring the gentle slope. Sometimes you’ll find leaflets in the covered metal box at the trail’s beginning that describe the flora along the way. Whether you find them or not, there’s plenty to ponder and take in without knowing the names of all the plants along the way. This loop trail is only a bit over half a mile in length, climbs about a hundred feet from the start and perfect for all ages and abilities. The Lightning Ridge Nature Trail travels underneath mature Jeffrey pines and black oaks, at times switchbacking amongst whitethorn chaparral (buckthorn) and even ascending the slope by means of steps made of landscape timbers. Over the years, our family has often used these steps as little seats to look out over the nearby desert with its’ ever-changing palette of color and shadow. One of the unique qualities of this loop trail is the constant grand views of the Mojave Desert to the north, Mount Baden-Powell toward the west, the open canyon country of the East Fork of the San Gabriel River to the south and, of course, Pine Mountain, Dawson Peak and Old Baldy to the east.

A view of the beginning of the Lightning Ridge Nature Trail. This short loop trail is a wonderful introduction for all ages into the landscape and flora of the San Gabriel mountains high country.

As the trail circles back in on itself and joins the PCT for the return, take a little time to rest on the overlook bench, taking in the fine views of canyons and peaks. Much of the Sheep Mountain Wilderness area is directly out front of you from this ridge top perch. One of the range’s most isolated and challenging peaks, Iron Mountain (elevation 8,008′), can be seen straight out to the south at the end of lonesome West San Antonio Ridge, which comes off of Mt. Baldy to it’s right (west). Iron Mountain’s nipple shaped summit is easy to identify from this vantage point. When you’re ready, return back to the beginning by way of the PCT. You’ll pass by fallen giant tree trunks, bleached smooth by the high elevation sun and wind. A great trail to experience at sunset!