Hike Circle Mountain without having to leave Wrightwood! If you live in or near Wrightwood, this local mountain is in just about everyone’s skyline on any given day. The view along the way, not to mention at the summit, is a superb 360 degree panorama. In less than a mile, you’ll climb about 800′ to the top. Some parts of the trail are hard-packed sand and super steep. It’s easy to slip, especially on the descent, so I highly recommend bringing trekking poles.

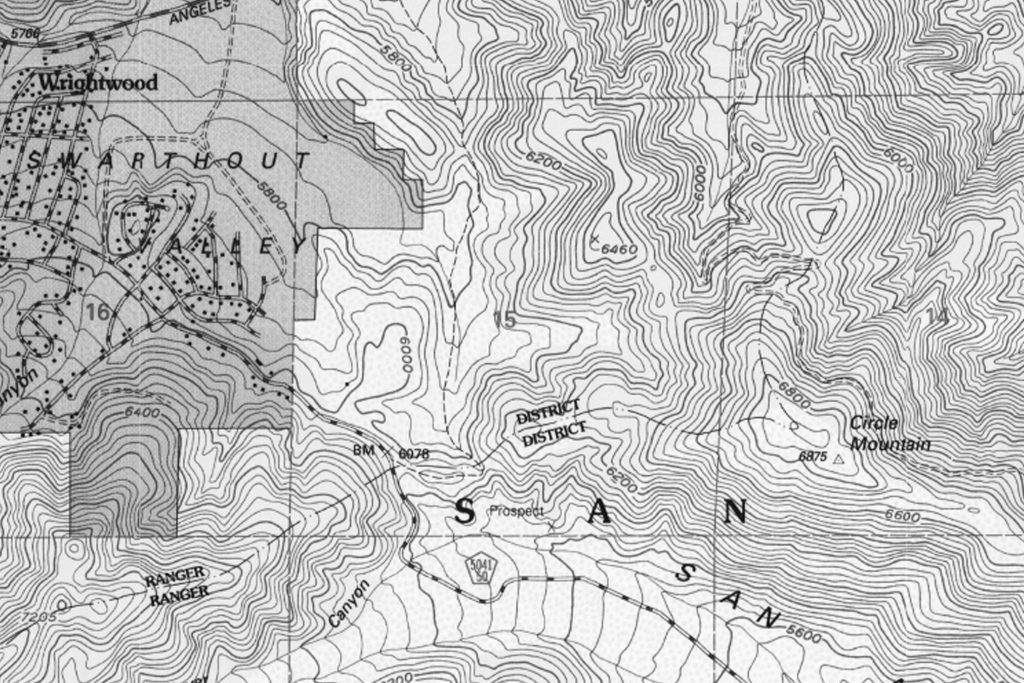

The route starts at a shiny white, heavy duty Forest Service fire road gate, at the crest of Lone Pine Canyon. If you live in Wrightwood, it’s that gate on your right hand side when you reach the very top of Lone Pine Canyon Road before coming back into the village from the freeway. You might even know the area at the fire road gate as “Helicopter Hill.”

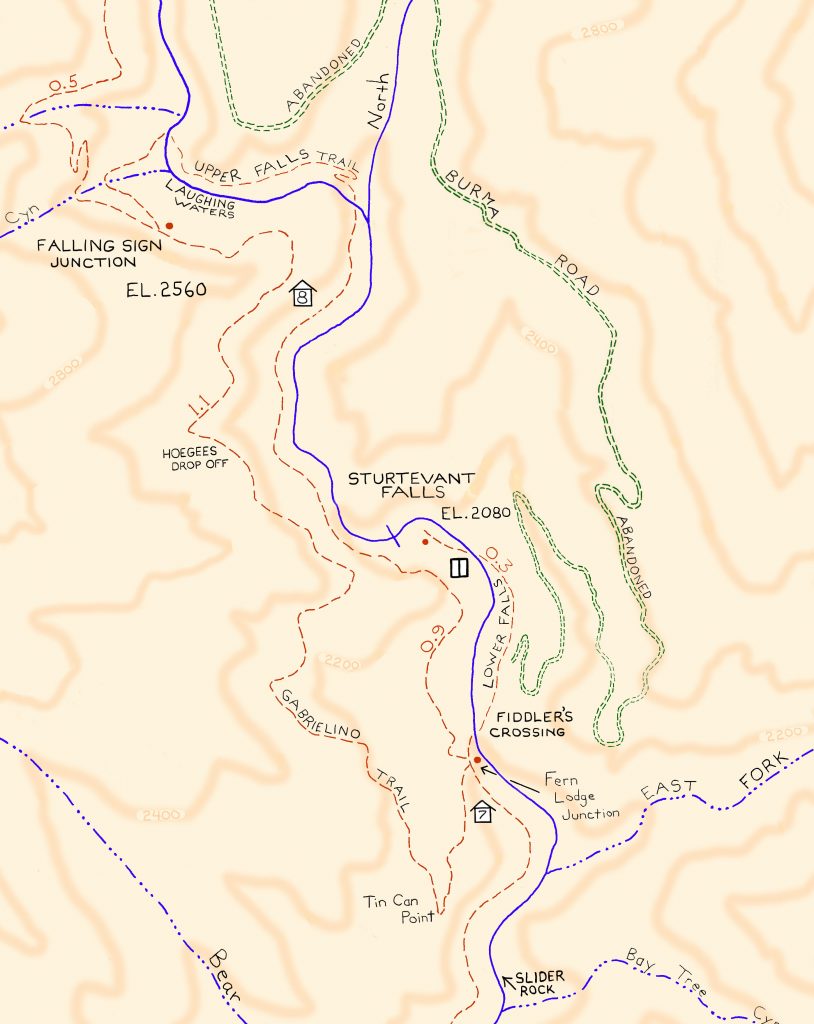

Just walk around the gate and follow the fire road eastward for a few minutes before reaching a barricade of boulders, marking the drivable end of the world’s shortest fire road. From here, the little sandy path drops down a little and continues along the exposed the ridge top before your climb begins in earnest. After the initial steep climb, the trail levels out a bit before you begin the second pitch. The Blue Cut Fire really burned off a lot of brush, including scrub oak and a number of pines. Despite this, plants are coming back. There are hardly any places to duck out of the bright sun, so bring a good sun hat and plenty of water. You’ll pass by clumps of Poodle Dog Bush, recognized by its’ ragged leaf margins and pungent scent. Also, look for Fremontia (flannel bush), chamise, yuccas and buckwheat. The chaparral that grows here is subjected to day after day of intense sunlight.

Here and there, as you climb, you’ll spot Jeffrey and Ponderosa pines with fire scars at their bases, yet their crowns blaze deeply green against the cobalt blue sky that only the high elevation can provide.

Something to know about Circle Mountain, is that its listed on the Sierra Club’s Hundred Peaks Section “peak list.” The list was created by Weldon Heald back in 1941. Throughout the decades, those attempting to bag all 100 summits, make a visit to our backyard mountain.

After reaching the summit, Joanie and had our lunch in a little glade of grasses amongst a grouping of tall pines on the north side of the mountain. From there we looked off into the hazy distance of the Mojave. The gentle summery breeze combed through the green boughs above. A little bit of heaven just minutes from the start. As we descended, the treat of one of the most unique views of Wrightwood and its’ Swarthout Valley was laid out before us. This little hike, though steep, is one worth making the time for.