View of Monrovia Peak from Manzanita Ridge just below the Mt. Wilson Toll Road.

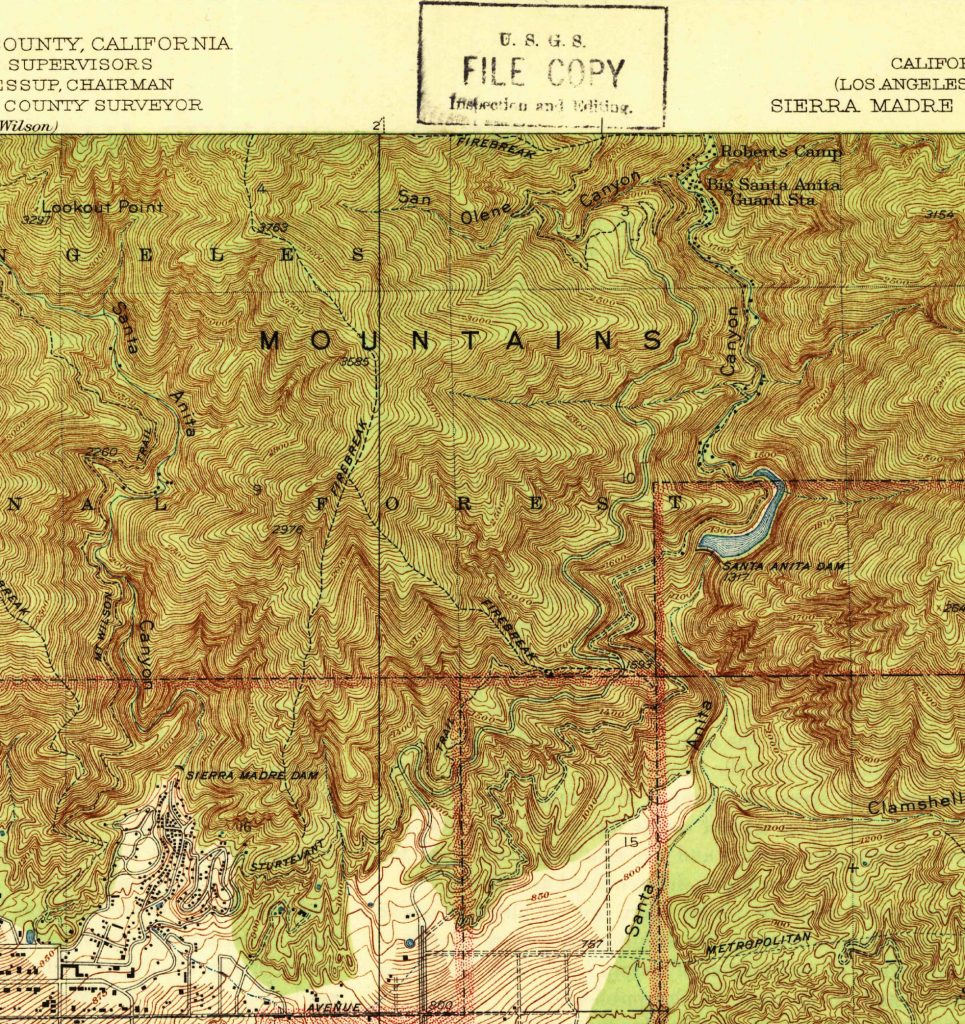

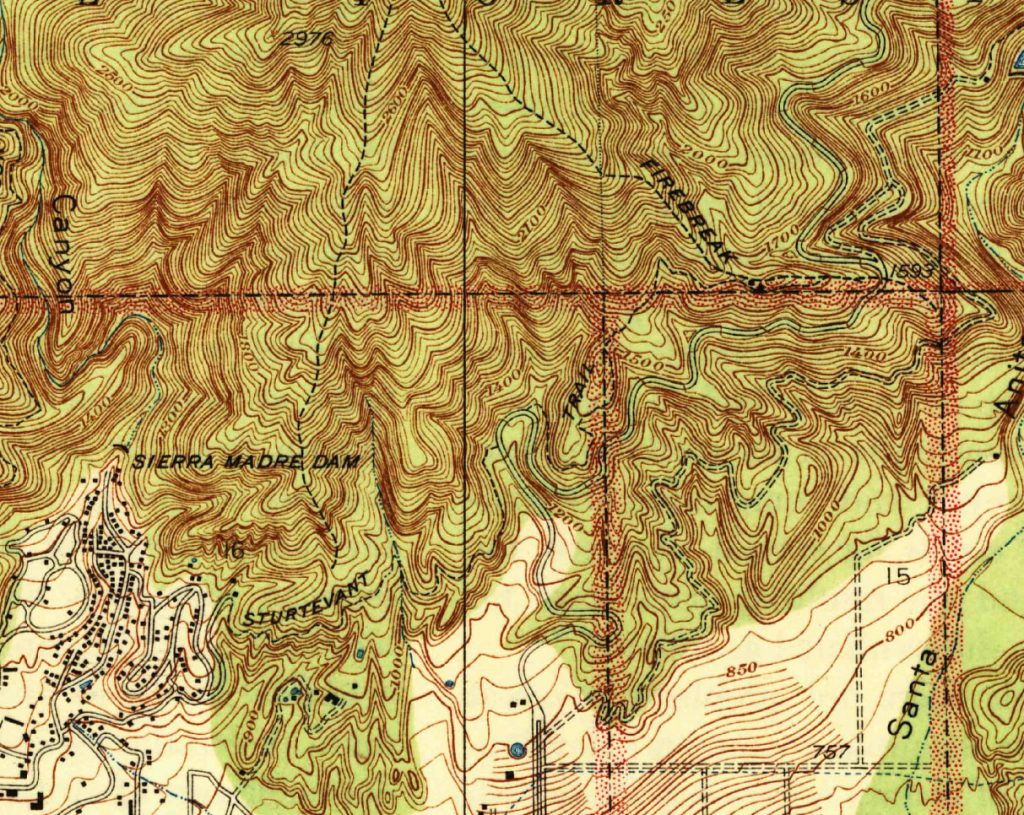

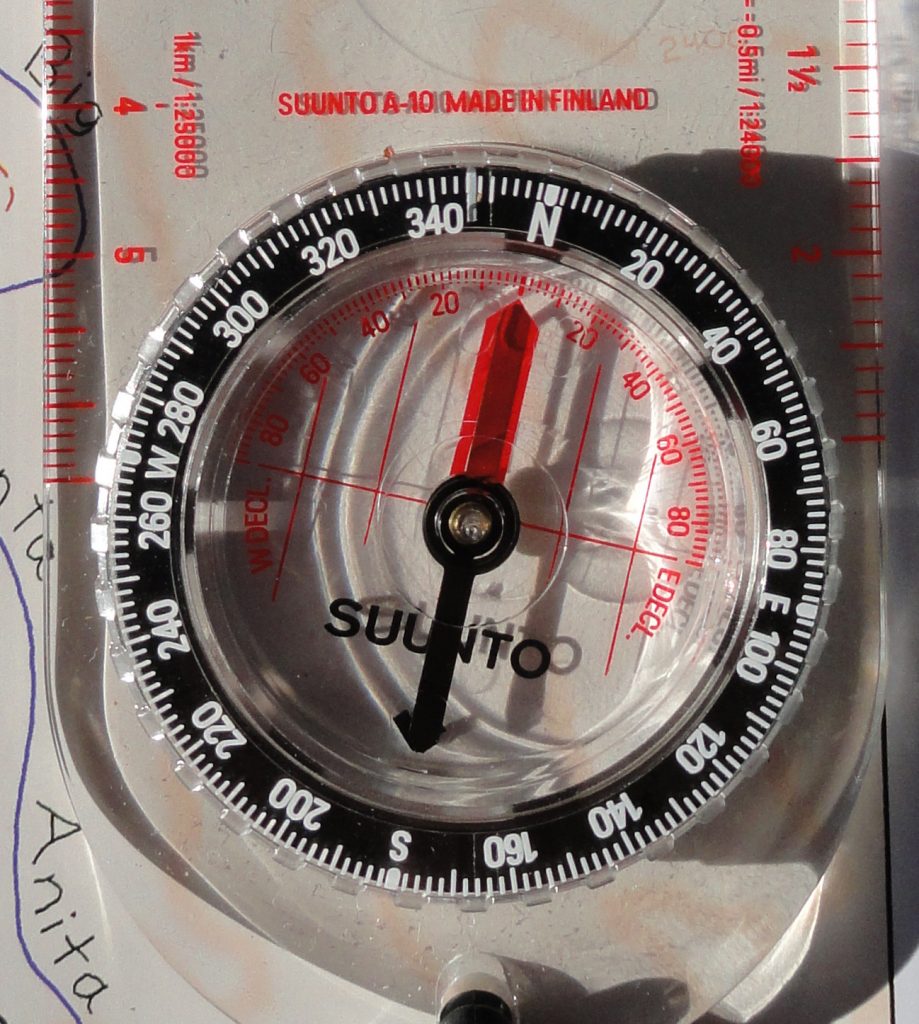

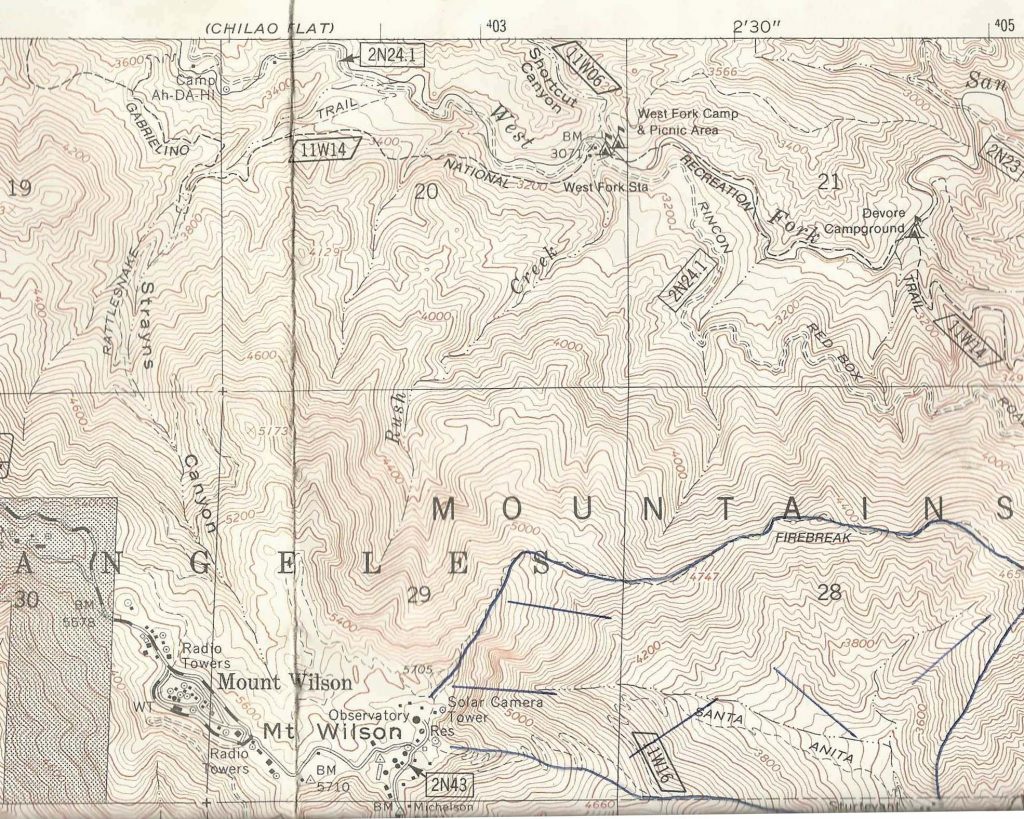

Any way you go, Monrovia Peak makes for a long and unforgettable hike. It’s a bright, clear day in mid February as I start out on the Lower Clamshell truck trail’s eastern terminus off Ridgeside Drive in Monrovia. We’re in our 4th year of drought and not much of winter has come. I’m loaded up with three liters of water, lots of food and my wife’s trekking poles. Most of the hike is on the 7.5′ Azusa quadrangle and just a sliver is covered by the Mt. Wilson map to the west. I’m old fashioned, so, of course, I’ve brought these two paper maps and my orienteering compass. For me, this is the way to navigate, to make decisions.

The route taken up the brushy ridge separating Clamshell Canyon from Ruby Canyon.

Walking on the fire road is the easy part, beginning the climb up the ridge dividing Clamshell and Ruby Canyons is the tough part. From a high point on the fire road, where it intersects the ridge, I turned right (north) and began ascending the shrubby ridge in steep pitches. The high-rises in L.A.’s financial district were in sharp relief, the warm air being so crystal clear. The trekking poles that Joanie encouraged me to use soon had become essential due to the steepness. Sweat was pouring off me as if it were summer and the sunscreen had already managed to sting my eyes. It seemed that I’d plod up the clay-like earth, pocked with gullies for a few minutes and then do that lean on the poles, staring at the ground while letting my heart slow down. This pattern would repeat and repeat, again and again, throughout the day. The pungent scent of black sage was all around. It’s funny how olfactory memories are in some way the most salient reminders of places from our past. I kept reliving a hike behind the Santa Fe Dam and up the San Gabriel River bed past the 210 Freeway some years ago which made me think of the time we lost our dear friend George Geer. Hikes up the switchbacks of the abandoned Burma Road made their return, too. Following and repairing the old crank telephone line up and over the ridge between the Winter Creek and Big Santa Anita Canyon. Different hikes with a common scent. The views out and over the valley began to become more and more expansive. Eventually, it was possible to see the ocean along with the freighters that were anchored off Long Beach. Restless freighters, waiting for a berth. And so it was, the pattern had now become plodding a short distance and resting amongst black sage, white sage, ceanothus (wild lilac), sumac, buckwheat, mountain mahogany, chamise and occasionally manzanita all intermixed with the myriad of memories and thoughts that are ever-present when we’re by ourselves. The constant views all around and down into the San Gabriel Valley kept happening amongst the thoughts from within.

“Selfy” in shadow form while ascending ridge from Monrovia.

The ridge soon gave out to a steep scramble up south-facing mountainsides. The route was little more than a wiggly trace between the brush. This trace is actually visible from the freeway. The hoof marks of deer were imprinted in the dried earth. Hawks, predominately red tails, floated on the warm updrafts. They seemed to slip and slide effortlessly high above the steep, chaparral clad slopes, searching and searching in some kind of an eternal daydream. I thought just how much the landscape seems unknown to me now since starting out from this same point back in 1985. Hard to believe it’s been about 30 years since last trying Monrovia Peak, coming within about a half mile of the summit and turning around. It was while on Christmas break from Humboldt State that my mom drove me up to the start of today’s hike. That day was filled with miles of walking ridge tops and fire roads before finally arriving at Rankin Peak under gray December skies. Monrovia Peak loomed just a short distance to the north and east, not far off… and, yet, it just wasn’t going to happen that day. Thoughts of Mom, Dad and Nick all swirled around my head as the slope finally gave way to a ridge top, the southern end of the Clamshell. Several ridges on my left and right came together, culminating in a view of views. And on I waded through tall grasses and the ever-present chaparral.

Mount Harvard and Mount Wilson as seen from Clamshell Ridge.

Chantry Flat along with First Water Trail and road down to Roberts’ Camp as seen from Clamshell Ridge.

The end of the Upper Clamshell truck trail was now visible below the ridge top. Grass grew in the center of its’ light colored trace. A lonesomeness seemed to emanate from its’ dead ended spur, high across from Chantry Flats. Surely, deer, black bear, coyotes, mountain lions and perhaps even the occasional mountain biker had been making use of what was seldom maintained for trucks. The view to the west encompasses the San Olene truck trail, Chantry Flat, Mounts Harvard and Wilson. The Pacific was gleaming in the mid-day sun, while the Palos Verdes peninsula seemed to divide two oceanic worlds. A subtle, yet substantial shift between the ’85 trip and now had taken place. Instead of following the upper truck trail across the east wall of the Big Santa Anita into the East Fork toward Spring Camp, I was following the ridge top, trying to stay true to the divide. Following the ridge was at times just about impossible to follow due to the thick brush. The ups and downs took their toll. Even though this route was slower than walking a fire road, it carried with it the alpine feeling of being on top of something that didn’t easily give itself away. Wild and rough. And it came with a surprise. Clamshell Peak. Clamshell Ridge is the watershed divide between Big Santa Anita Canyon to the west and Monrovia Canyon to the east. The ridge pretty much trends north and south until reaching Clamshell Peak, a high point where the ridge begins to trend eastward toward Rankin and Monrovia Peaks. If you travel the truck trail, you’ll miss this peak. Clamshell appears on the topo map as being just a bit higher than 4,360′ in elevation. Looking out from this brushy mountain, the final undulating ridge out toward Monrovia Peak presented itself. There is an impressive view straight into the entire Winter Creek from up here as well. I had entirely missed this place the first time around.

Summit register and vault box on Clamshell Peak. The register is stored inside box.

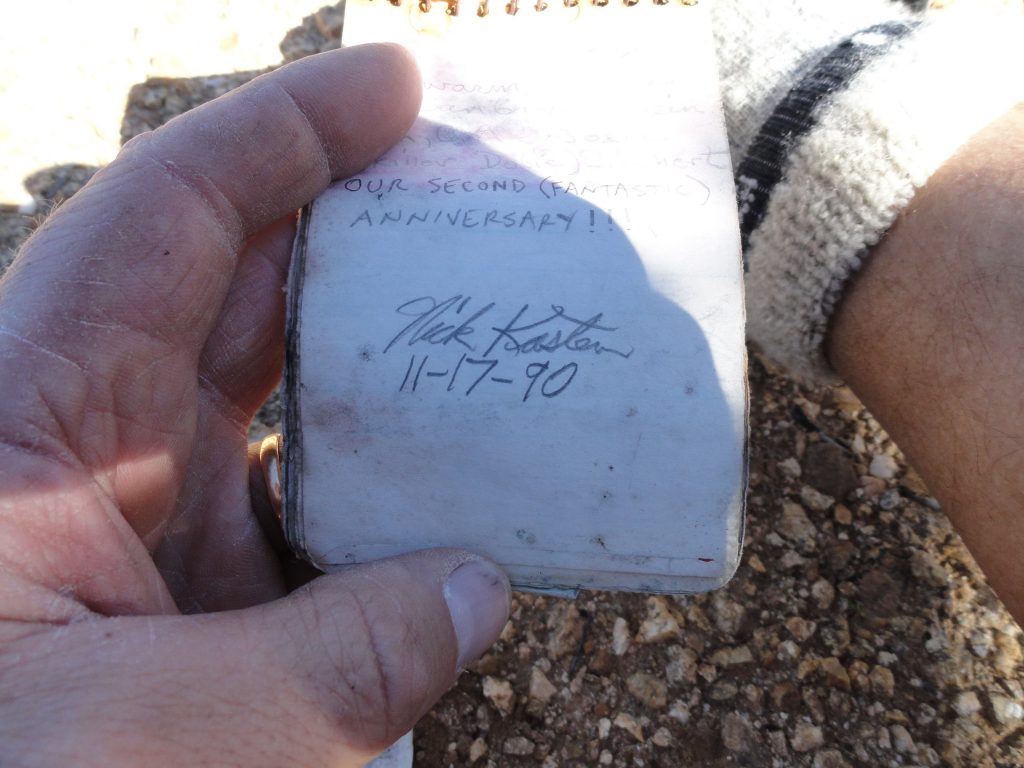

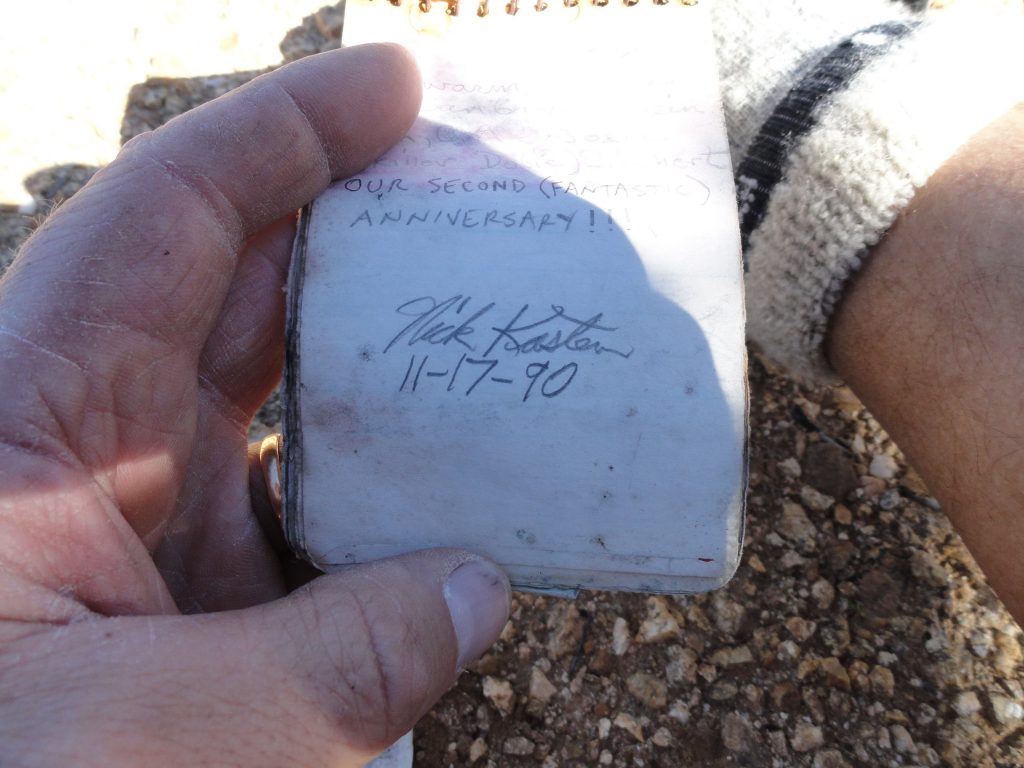

What really caught my attention was what appeared to be a U.S. Forest Service vault box of some sort on the summit. Dragging the rusted diamond plate away from the opening, there appeared to be two red painted cans nested within one another. An old school summit register wrapped in ziplock bags! In the shade of a manzanita bush, I had thumbed through two steno notepads. The one marked “old book” had signatures of visitors going back to 1987. A signature from November of 1990 stunned me. It was my late brother Nick’s. I did not remember ever hearing him tell me of his visit here. Back then, he would have been about 27 years old, in his prime and all over the San Gabriels. What route he’d taken to get here I’ll not know in this life. The route now shifted eastward and steeply down to the fire road. So, for the rest of the day, he and I hiked together, again, through the trees, then up and over more miles of ridge tops. He was young, healthy and relaxed. I talked and he listened while the sunlight had shifted a bit. Walking much of this old firebreak had become easier on my head although my legs seemed to have less and less in them. We came to a small clearing at the base of some mammoth Big Cone Spruce and sat down in the pool of gold light, the kind that appears later in the afternoon. I had ran through two of the three Nalgene bottles by this point and had a little snack. The thoughts had turned toward Rankin Peak and I kept going back, back, back through the years. That’s what we do, I suppose, in our mid years. I would not be alone for the rest of the hike.

My brother’s signature found in summit register on Clamshell Peak. Nick Kasten lived from 1963 to 2014.

Eventually passing a point on the ridge that appears as “Mack” 4,364′ and paralleling the fire road, the final pitch to Rankin Peak drew near. It was all so close visually, yet closing the gap seemed never-ending. I’m always out hiking, like always…. yet, today it was like this was the first time ever being out in the mountains. That first great climb out of Monrovia in the warm sunlight must have really taken its’ toll on me… On I walked through grasses that had already grown blonde in the dry winter days. The memory of how that ridge appeared from Sturtevant Camp’s heliport was playing in my mind. I had known the changing colors and its’ unmistakable silhouette as part of all that encompassed and framed our existence during those years in the upper Big Santa Anita. Being part of that scene now was like being in two places at once, looking back at myself from a time gone by.

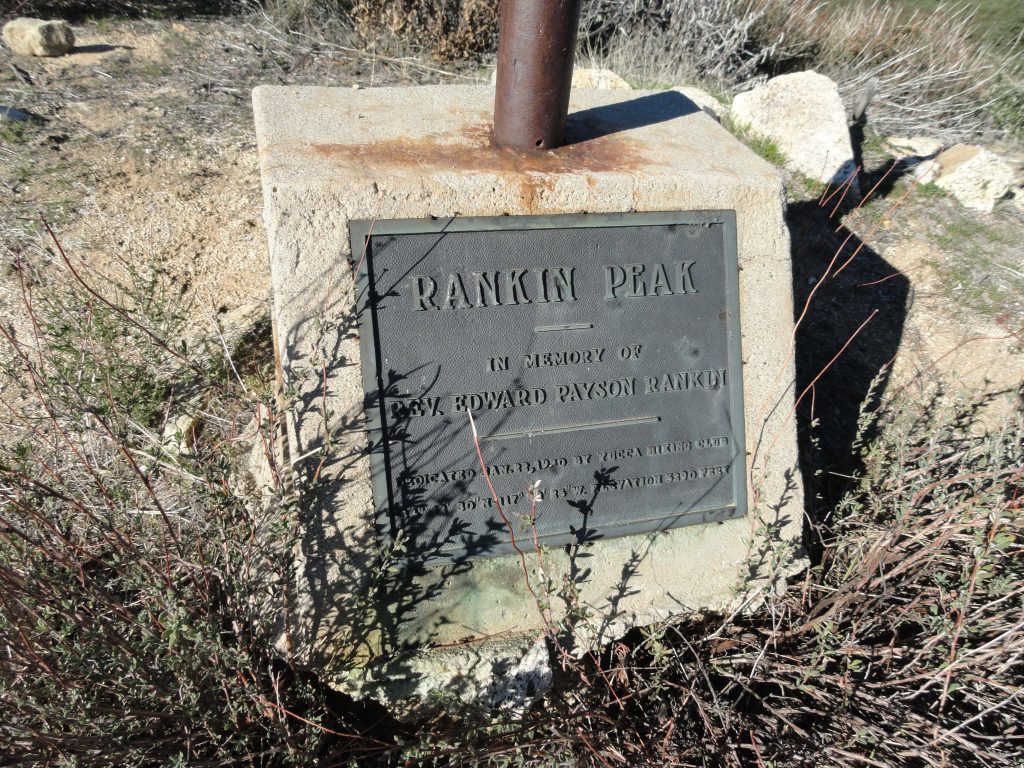

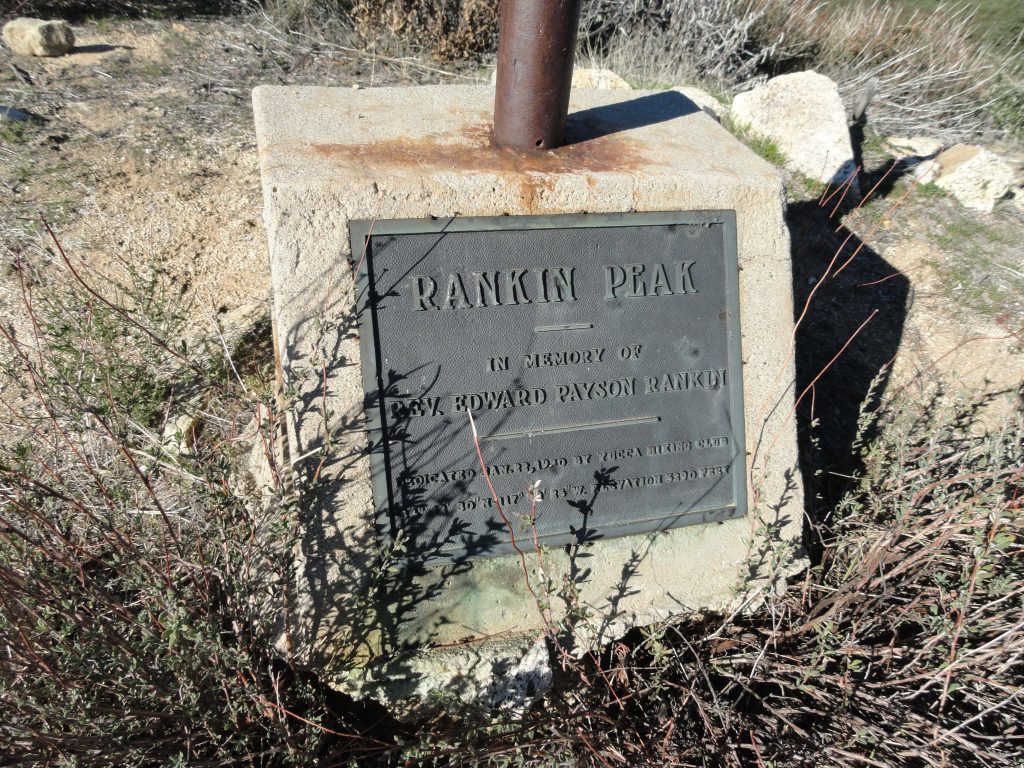

The old flagpole footing with plaque on summit of Rankin Peak. Placed here by the Yucca Hiking Club in the 1930′s.

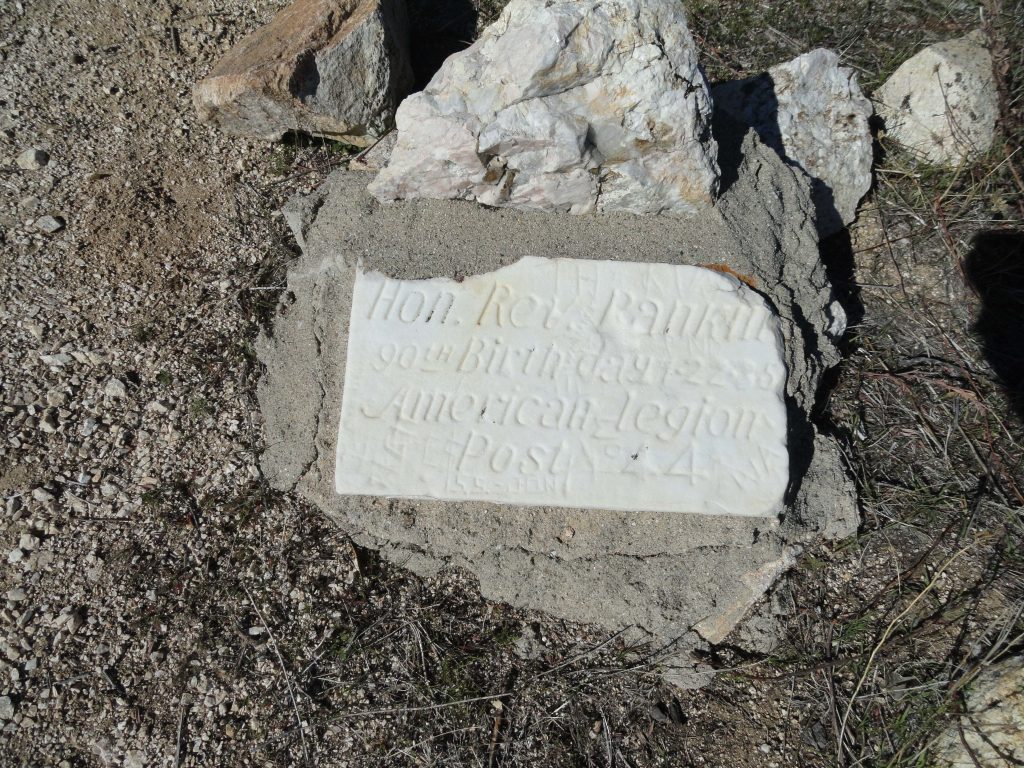

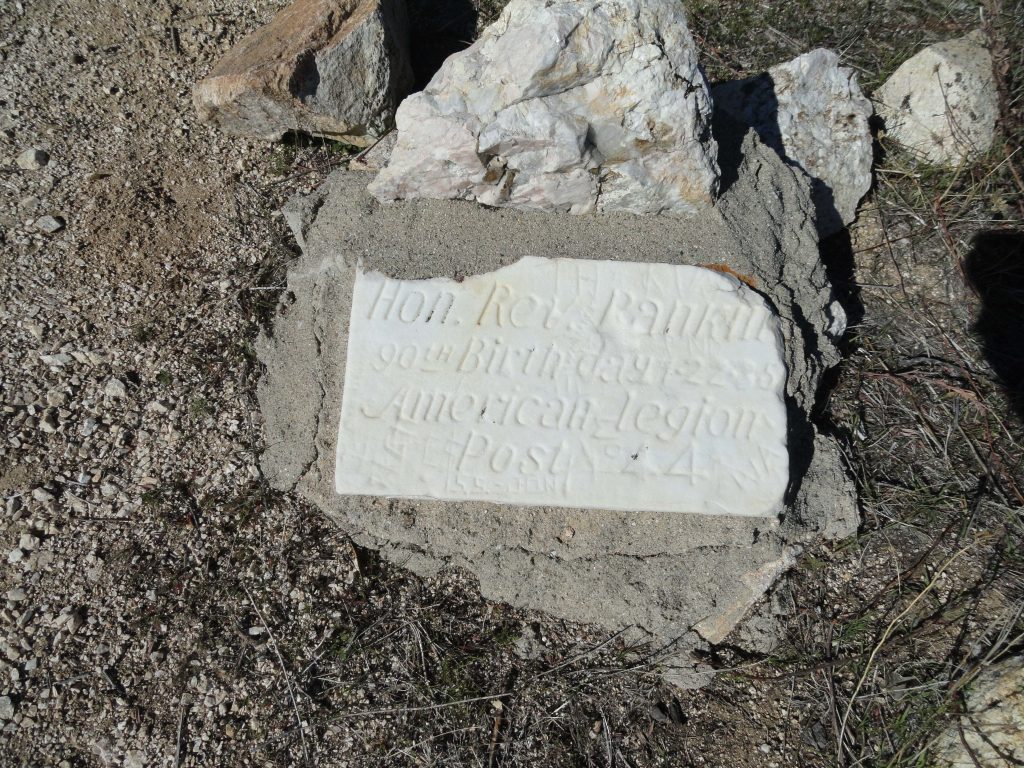

Arriving at Rankin Peak looked nothing like I had remembered it. There were fewer trees than my mind had recollected. Low, scraggly brush crowned the summit and the remnant flagpole was low and bent way over. Two monuments had been placed here commemorating Reverend Rankin. The Yucca Hiking Club had placed the brass plaque and white marble marker here back in the 1930′s. This was Reverend Rankin’s hiking club that had developed the memorial. Will Thrall, protector and scholar of the San Gabriels, editor of Trails Magazine, a periodical for people hiking our local trails back in the 1920′s and 30′s, routinely included articles from the Yucca Hiking Club out of Monrovia. Seeing places like this and the need for immortalizing memory brings to mind just how much we all need the mountains and each other. Some things will never change.

Very top of Monrovia Peak. Note the benchmark adjacent to my pack. The red can is the summit register.

Old tombstone style marker on peak commemorating Reverend Rankin’s 90th birthday.

It was here where I turned around all those years ago. Not this time. I had to finish this thing once and for all. And on I went. There’s the descent, then a climb up an unnamed bump, followed by another descent to a saddle which is then followed by a final and steep climb to Monrovia Peak. Finally at the top of Monrovia Peak’s 5,409′ summit. Whew… The summit is small, like 20′ across or so, and is basically a low bump or mound above a circular track most likely created by a bulldozer many years ago. I suppose the firebreak builders didn’t want to disturb the summit benchmark and I’m glad they didn’t. I sat down between a small manzanita and mountain mahogany bush and, of course, went through the summit register. There had actually been a family of three up there earlier that same day! The sun had fallen even lower now, the shadows lengthening across the canyons. It was time to take another good look all around. Red Box saddle at the upper end of the West Fork of the San Gabriel River was visible in the west. The long rambling ridge of Mounts Pacifico and Gleason framed the north horizon out toward the desert. Devil’s Canyon and Bear Creek in the San Gabriel Wilderness filled in the scene toward the northeast, while Mounts Williamson, Throop, Baden-Powell, Pine, Dawson and finally Baldy filled the skyline toward the east high country. And way off to the east and south, San Gorgonio, San Jacinto and Saddleback poked up through the fine marine haze. Not a finer view could I have expected to have had anywhere. One more look around and the descent began. I followed an old and very steep, rutted firebreak down toward where the Edison high-tension power lines cross over the Rincon – Red Box fire road toward the north east of the summit. Lonesome, shaded country. After about a half hour, I was walking down fire roads that lead toward Monrovia Canyon Park. It’s about 11 miles of fire roads down to where I’d left the car earlier that day. The key to getting back down to Monrovia and not San Gabriel Canyon or even Duarte, is to follow the Rincon – Red Box road east to your first option on the right, which appears on the topo map as the Upper Clamshell truck trail. Passing through a gate, take this road down through Cold Springs Canyon traveling underneath the Edison power lines. You’ll stay on this road for quite awhile until finally arriving at White Saddle. At the saddle, take another right, bearing down into Saw Pit Canyon. There’s a metal sign at this critical junction which indicates that you’ve still got another 4.8 miles to go… By now I was walking with moonlight as well as the light coming up from the city. Often it was possible to not have the flashlight on, unless I was under the cover of trees. Mile after mile I hummed little songs and songs blessing those who I had known over the years.

Looking east toward Mt. Baldy from Monrovia Peak’s summit.

Dropping into Deer Park, while coming around a switchback, the sound of wind could be heard. No, that wasn’t wind, it was water! I had a Life Straw for drinking untreated water. Things were looking up. Unfortunately, getting down to the stream in the darkness required going down a low cliff covered with nettles and poison oak, so on I went with aqueous dreams. Further down near Trask Scout reservation, a tremendous chorus of frogs celebrating their watery existence could be heard, yet it appeared that uninvited visitors of the two-legged variety were not welcome on the private property, so on I walked. Eventually passing by the Saw Pit dam, I could look down and hear the water spilling out of the base of the dam, yet no way to reach it from my great height… By now this had become comical and my sense of thirst had almost gone away. I walked down the Monrovia Canyon Park road along a barbed wire fence that separated me from the creek which I could hear. It was totally hilarious! Perhaps I was mildly dehydrated and had lost touch with my predicament. At any rate, I finally found our car and drove straight to Chantry Flat and drank as much water as I could get from the little drinking fountain out front of the ranger station.

Monrovia Peak as seen from the communities of Arcadia and Monrovia. Photo taken by Dave Nickoloff at the time I was on the summit.

A short distance later, I was at our cabin telling Joanie about the great adventure. The ice cold bottle of beer that emerged from our little gas fridge was beyond heavenly. Glass after glass of spring water had become the chaser. Candle light cast its’ soft, warm glow all around. A tea light on the mantle cast its’ glow on some old framed black and whites I’d taken of my parents, brother and sister. The sound of our little stream played in the background. I was here and it was good to be home.