Phone line and insulator detail of crank telephone system. This location is at the top of Sturtevant Falls on the Upper Falls Trail.

Have you ever wondered what that green wire is running from tree to tree along the trails at Chantry Flats? That green wire is part of the Chantry Flats crank telephone system over six miles in length. This remnant phone system goes back to a much earlier time in the Angeles National Forest’s history; a time when the Angeles Crest Highway had yet to be built and trail resorts were thriving during the “Great Hiking Era.” It was a time when much of southern California was still agricultural and hikers often took the Pacific Electric red cars (trolleys) to trailheads before embarking upon the multitude of paths in the San Gabriel mountains.

The crank telephone system connected most of the old trail resorts, such as Hoegees, Sturtevant’s, Roberts’, Fern Lodge and First Water Camps in the Big Santa Anita Canyon. Many of the private cabins were also connected to the phone system, not to mention Guard Stations manned by the U.S. Forest Service. The phone line also ran into the “backcountry” to places like the West Fork of the San Gabriel River and Coldwater Canyon near Strawberry Peak. It went to Mts. Wilson and Lowe, up and down the Arroyo Seco Canyon and other canyons too numerous to include here. In short, the crank telephone system was a vibrant, reliable form of communication for a time gone by.

Split ceramic insulator carrying the 12 gauge phone line. Upper Falls Trail, Big Santa Anita Canyon.

Nowadays, in canyons other than the Big Santa Anita and Winter Creek, you’d never know where to look for evidence of this historical technology in the Angeles’ early days. If you’re hiking up the Sturtevant Trail toward Mt. Wilson, look for a number of remnant split ceramic insulators still dangling on rusted wire from the oak trees not far up canyon from Sturtevant’s Camp. In some cases, you can see where the white, round insulators that used to be nailed directly into tree trunks are now being consumed by the still growing trees. Just a nubbin of an insulator still protrudes from trunks of oak and spruce, sort of appearing the way a white spool of thread might appear if you looked at it “on end.” It’s center attachment nail long corroded and missing.

The phone line in the Big Santa Anita currently travels between the Adams Pack Station at Chantry Flats down to First Water and then up stream to Sturtevant’s Camp four miles north and west of there. Another section of line branches off from Roberts’ Camp, which is where the hikers’ footbridge is located. From there, the line goes up the Winter Creek to a spot just up stream from Hoegees Campground. The line travels from tree to tree, supported by ceramic insulators. The line itself is 12 gauge and uninsulated, its’ core being made of steel for strength with a surrounding jacket of copper for conductivity. Connections between sections of wire are made with “butt-in” style connectors made of brass which are crimped into place. These connectors look like narrow little barrels that the line slides into before it’s crimped half way in. The next section of line is slid into the other half of the barrel and crimped as well for an airtight and, hopefully corrosion-free seal.

Crank telephone and battery in call box #8, Upper Falls Trail, Big Santa Anita Canyon.

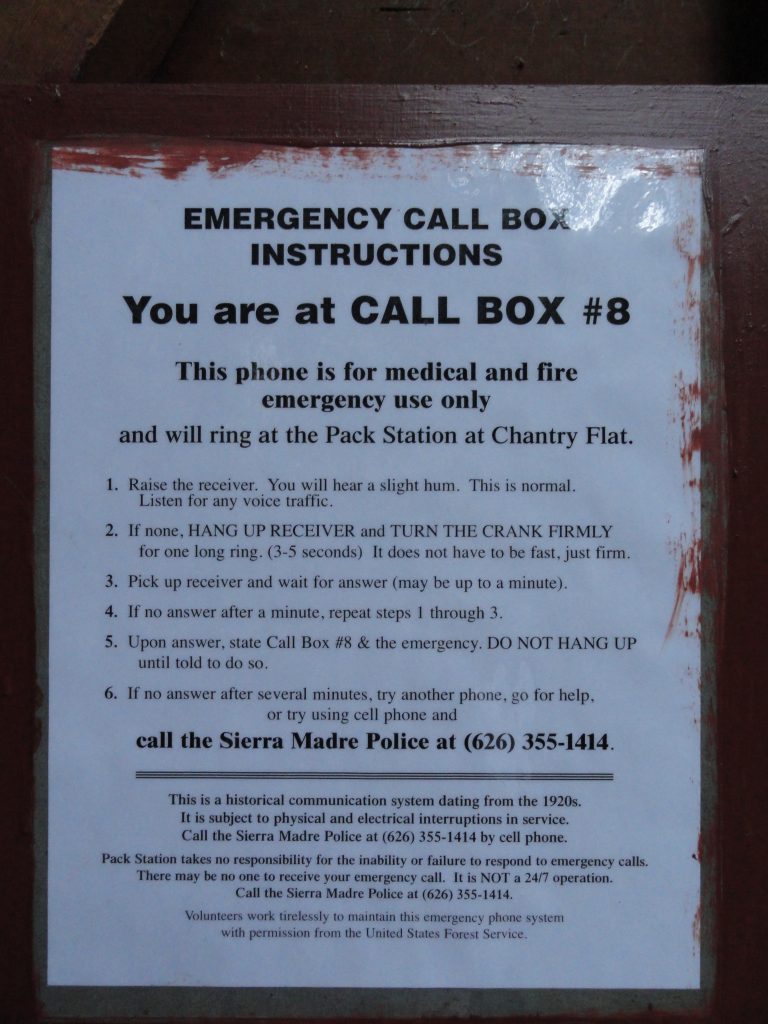

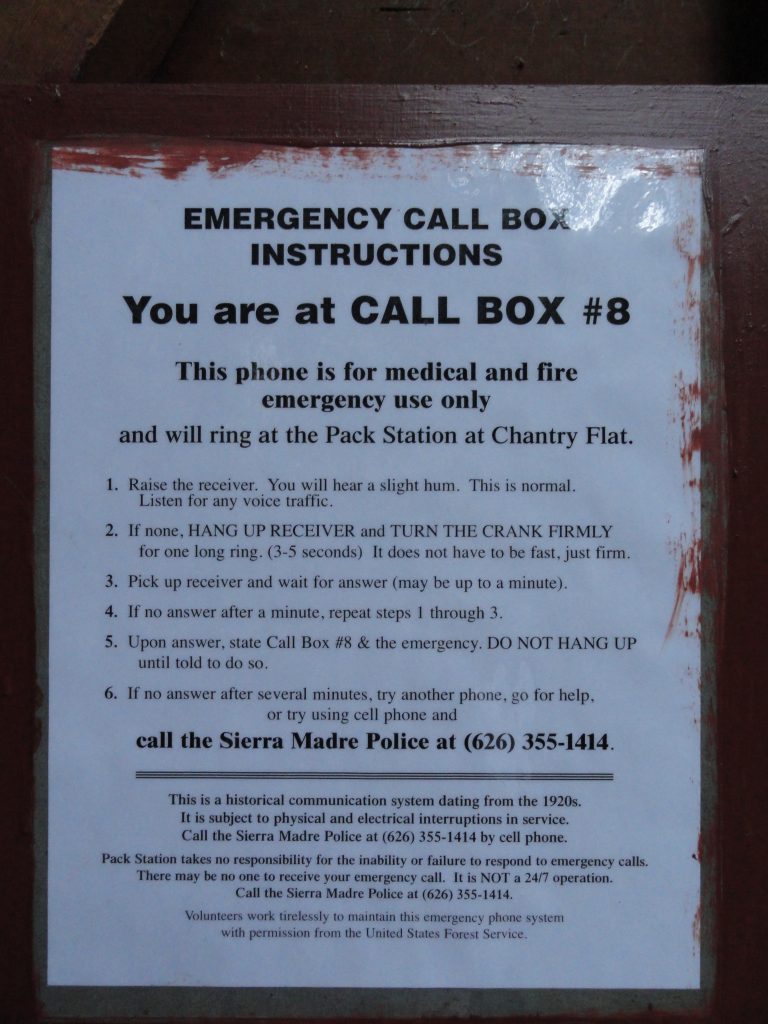

There are currently nine call boxes located alongside the trails with crank telephones and batteries in them. These call boxes are for emergency use, such as the reporting of fires or medical emergencies. The locations of these call boxes appear on the Big Santa Anita Canyon Trails Map by canyon cartography.com. A fair number of the cabins that you see along the trail also have crank telephones as well. You might be wondering just how one makes a call from one of these antique phones. Since there’s no dial at any phone, what you do is send a pattern of “rings” from your location that will tell the recipient of your call if the message is for them or not. For example, the Pack Station is “one ring”, Sturtevant Camp is “two rings” and any private cabin would be “three rings.” This is known as a party line and was quite common in rural areas of the United States up until the 1950′s and early 60′s. A ring is created when the crank handle located on the phone is turned rapidly as possible to generate voltage. (the crank handle is connected to a 2, 3, 4 or 5 bar magneto) So, say you’re calling a private cabin owner, you’d crank the handle vigorously several turns, pause…., then crank several turns, pause…, then several more turns. Now, stop cranking and just listen. Be patient. Chill out and wait a good minute for your party to pick up on the other end.

Call box #8, Upper Falls Trail, Big Santa Anita Canyon.

On a crank telephone, your voice is carried by battery power. There’s no need to keep cranking a phone when speaking – only to ring someone. Each phone is protected by a carbon block lightning protector. You’ll notice that the call boxes along the trail also have a 6 volt lantern battery attached to the phone. Originally, the phones were intended to operate on 3 volts, not 6. The batteries were cylindrical, dry cell 1 volt types in series. It seems that for decades now, we’ve been using the lantern batteries without damage to the phones. Also another detail in regard to this type of system is that there’s only one wire traveling from tree to tree. All phone systems have a circuit that must be completed, thus the wire pair we’re all so used to seeing. So, where’s the other half of the wire pair? It’s the earth. Each phone or call box must be grounded some how. Sometimes there’s a ground rod driven into the earth for this purpose, other times there’s a bare wire going into the stream or a ground wire’s attached to a cold water pipe. Good grounding’s important if you’re going to have a clear pathway for your phone to work and to be easily heard.

The call boxes that you see along the trails were built by the U.S. Forest Service back in the 1940′s, just after World War II. Each call box not only had a phone, but a water pump with a suction strainer and fire hose. There were also McClouds, shovels and other fire fighting tools. Back in the 40′s, 50′s and 60′s, it was expected that members of the recreating public be willing and able to fight wildfire if the need arose. The Forest Service also maintained the phones and phone line, climbing trees and restringing wire as necessary. Unfortunately, with budget cutbacks constantly hacking away at the Angeles’ operating costs, phone repair fell by the wayside.

Operating instructions for the Chantry Flats crank telephone system. Call box #8.

Fortunately, the Big Santa Anita Canyon Permittees Association, comprised of concerned cabin owners, took over the maintenance of the crank telephone system. This rural phone system is truly a last remnant of an earlier time in Southern California’s San Gabriel mountains.