This is a short story about hiking the abandoned Burma Road of Chantry Flats. You can see the route of this old road on the Chantry Flat – Mt. Wilson Trails Map, available on this website, or at the Adams Pack Station General Store next to the Chantry Picnic Area. This old road was once the carved out thoroughfare of cement mixers, bulldozers, skip loaders, cranes and more during the construction era of the check dams upstream from Sturtevant Falls. Today it rests quietly , slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

It was warm and mild out on the front porch of the cabin. A gentle breeze woke up the chimes hanging from the eve. The ringing was calm and faint. I set down my book, relaxed and yawning in the bright February sunshine. What to do? Maybe take a nap if I didn’t start moving or perhaps, hike up to the prominent switchback of the long-abandoned Burma Road. Only a mile and a half in from Chantry Flats, one can suddenly transport one’s self into a chaparral-clad wilderness of upward climbing.

So, I’m doing this crawl up a gully between two of our neighbors’ cabins. At first, like everything we don’t know the whole story of, it’s really easy. Lush, green grasses blow lazily about my boots as I plod upward. Shaded by blossoming bay trees, the air is sweetened by thousands of the tiny yellow flowers. Large and stately canyon live oaks begin to make their presence as I climb further and further from the Big Santa Anita Creek. The slope’s steepness increases and I’m constantly stopping and kicking into the moist, sandy slope. The one thing that I packed, the one thing that I’d really need for this trip was a pair of smallish pruners, or loppers, for cutting through brush. These became indispensable as my route began to be impinged upon by dense, dry tangles of brush. Several times, even the little folding pack saw came out for branches that were over a couple of inches in diameter. So, my pattern was often moving up the mountain gully a few paces, clipping and sawing, then pushing through the tiny opening to step up a few more paces…… I was soon high enough to see Mt. Harvard out across the Winter Creek Canyon. Chamise and buckbrush began to make their presence. This was the really hard going. Soon I was wading hip deep in black sage, which left its’ signature scent in all my clothing. Clutching at little twiggy limbs, I pulled myself up the final pitch to the old Burma Road and a fragrant, blossoming patch of rosemary.

Hoary Leaf Ceanothus

This same spot was visited by Richard Loe and I last spring. However, we had walked and climbed up the decaying switchbacks of the old road near Sturtevant Falls. That day we ran into three stout, black rattlesnakes gliding through piles of white rocks – all within a couple of minutes! This time, I was a good month earlier in the season, so rattlesnakes were the last thing on my mind. From the end of this switchback, I could make out the Pacific Ocean, while Catalina Island appeared to float on the hazy scene. After drinking a little water and shaking the chaparral fragments out of my clothes, the thought of how to return slowly made its’ way in. It was a sparkling, dazzling clear day. All courtesy of the mild Santa Ana winds. The startling clarity of vistas and the mild temps make Southern California’s mountains a paradise. I just wanted to stay out in it and make the day last. One thing for sure, the route back down the gully was doable, yet not what I really wanted to do. I looked across and down to Sturtevant Falls emerging out a gash in the white cliffs from my unique vantage point. It was decided, continue up the abandoned Burma to the where it enters the North Fork and then back down to the Upper Falls Trail. This would be a great way to make a loop out of my trip.

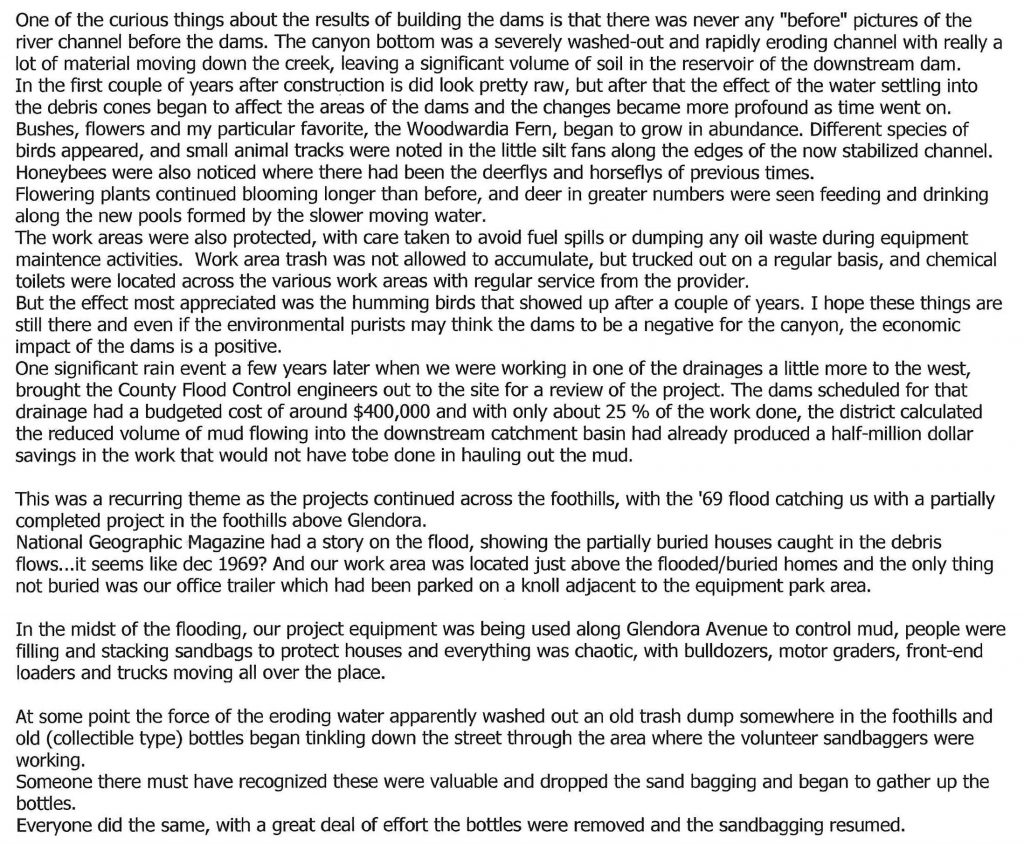

Close-up of blossoms, Hoary Leaf Ceanothus

There’s brush all over the Burma Road. In case you’re wondering what this road was all about, you can read a blog I wrote earlier on about the building of the check dams. Entitled, “How Did All These Dams Get Here?” The abandoned Burma Road shows up on the Big Santa Anita Canyon Trails Map. On I hiked, weaving through sumac, sage, yuccas, non-native pines and eucalyptus (planted by the Forest Service), manzanita and more. At one point I got mixed up and wandered off on some kind of spur road that must have dead ended. However, before that was figured out, the sumac was chest high and the beating through the brush had become relentless. There was a beautiful scene that just had to be photographed. It was a hoary leaf ceanothus (Ceanothus crassifolius) also more commonly referred to as buckbrush or wild lilac. One of the great things about the hoary leaf variety is that there are no thorns to be reckoned with! This shrub blooms usually from January through April and emits a sweet, sugary fragrance from its’ myriad tiny flowers along the branchlets. Right now, you can see lots of this beautiful plant blossoming on the slopes across the canyon from Chantry Flats. Not long after this, I was once, again, wading through the brush when I heard a dull, flat hiss coming from the ground near my left boot. It couldn’t be…. I looked down and saw an irregular opening in a boulder lodged in the ground. Perhaps a brother or sister of the Crotalus genus had been startled by my careless wandering… Time to back straight out and look for where the road really ran. It had been since 1977 or 78 when Howard Casebolt and I followed this same section of the road, so now it all seemed so new and fresh! Fortunately, I found where the road made a sharp hairpin and was soon on the right track. There were road cuts that were so deep (25-30 feet high) and narrow that the road was cool and damp. Gooseberry bushes even liked these spots. Dark green, plump grasses lay down in these dark, secret places. Eventually, I walked and scrambled along the road’s remains in the area I call the “Great White Scar,” visible not only from Chantry Flats, but much of the San Gabriel Valley below when you look up the mouth of the Big Santa Anita. Although the sun was nearly over the ridge by now, heat radiated out from the plane surfaces of jagged, white rocks. Thoughts of large, anxiety-ridden serpents occasionally filled my mind as I continued to hop from rock to rock and beating back more brush. Eventually I made my way to the large pine flat just above the North Fork confluence near cabin #94. Whew! The one thing I didn’t bring and began to wish I had, was a flashlight. Soon I was scrambling down the side canyon to the Upper Falls Trail in the gray and failing light in the canyon bottom. Arriving at the cabin, I chuckled to myself just how pivotal one’s decision to take a nap or go for a “little” hike can be.