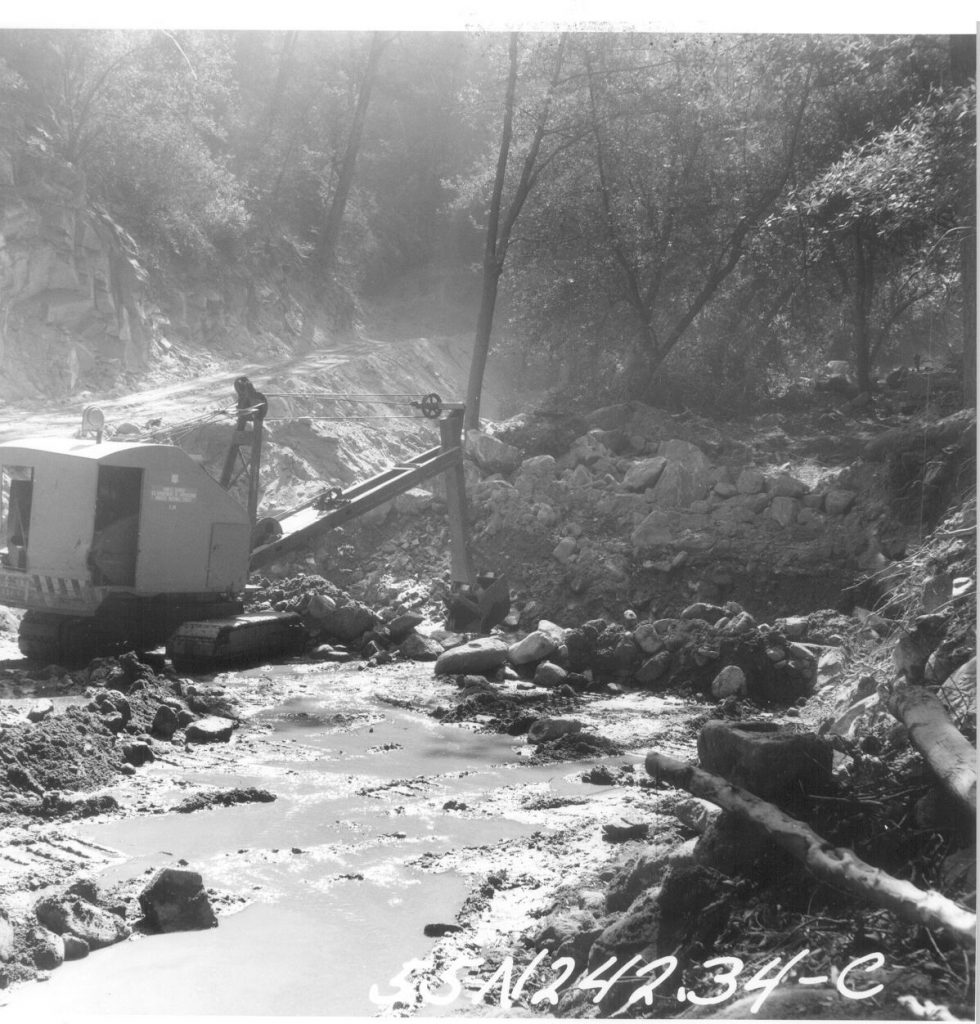

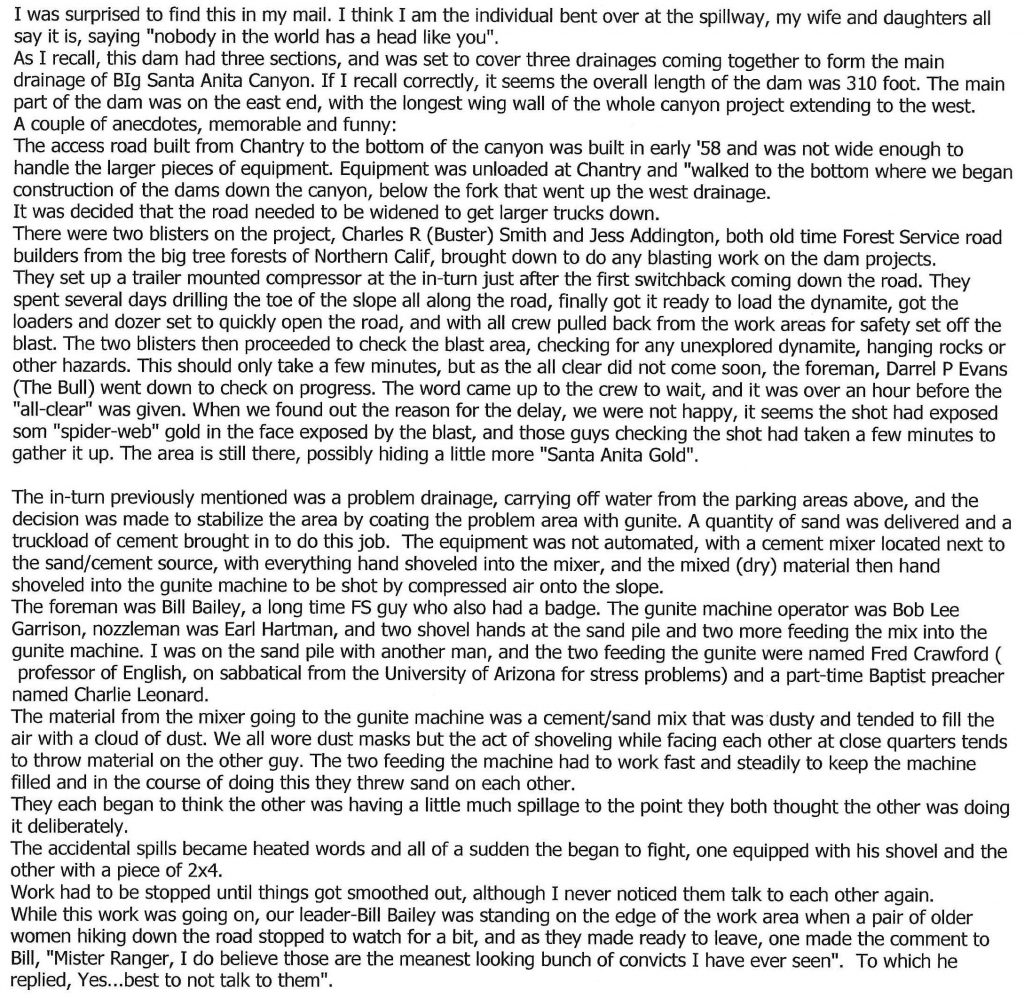

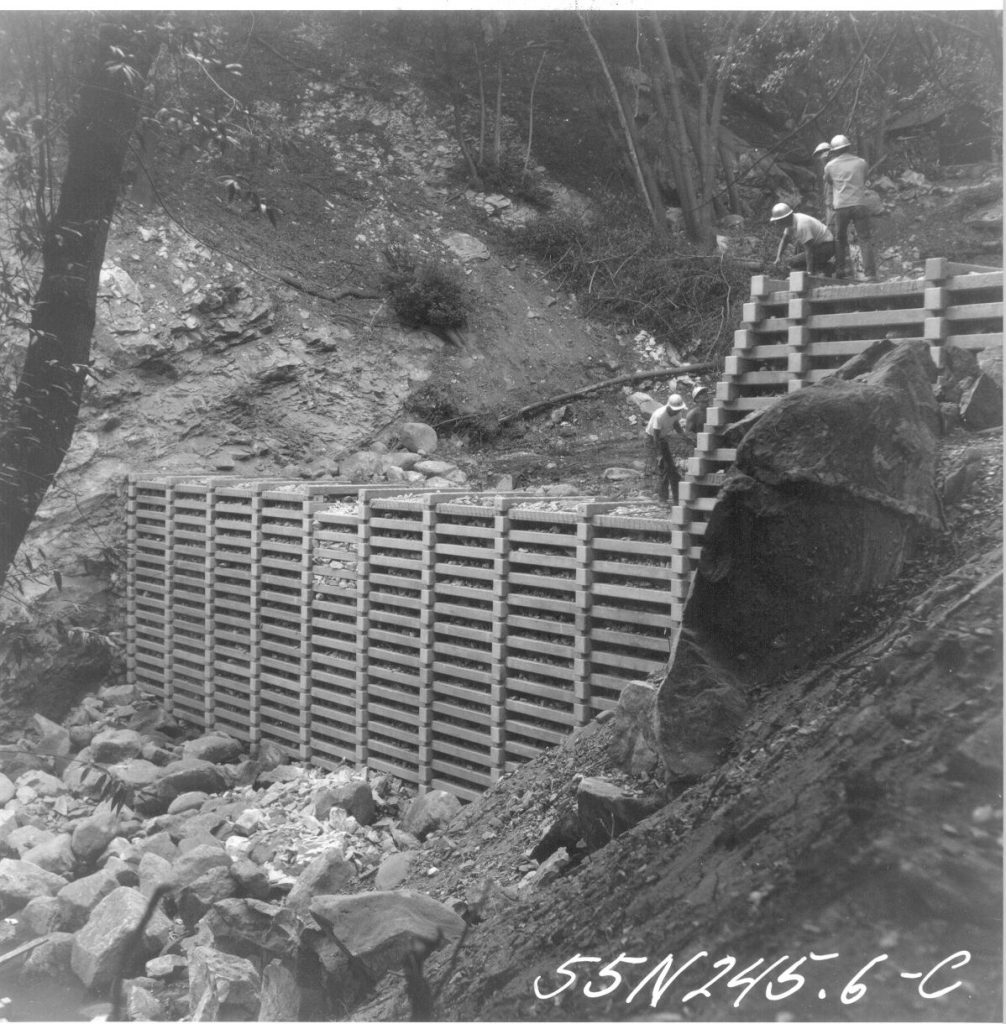

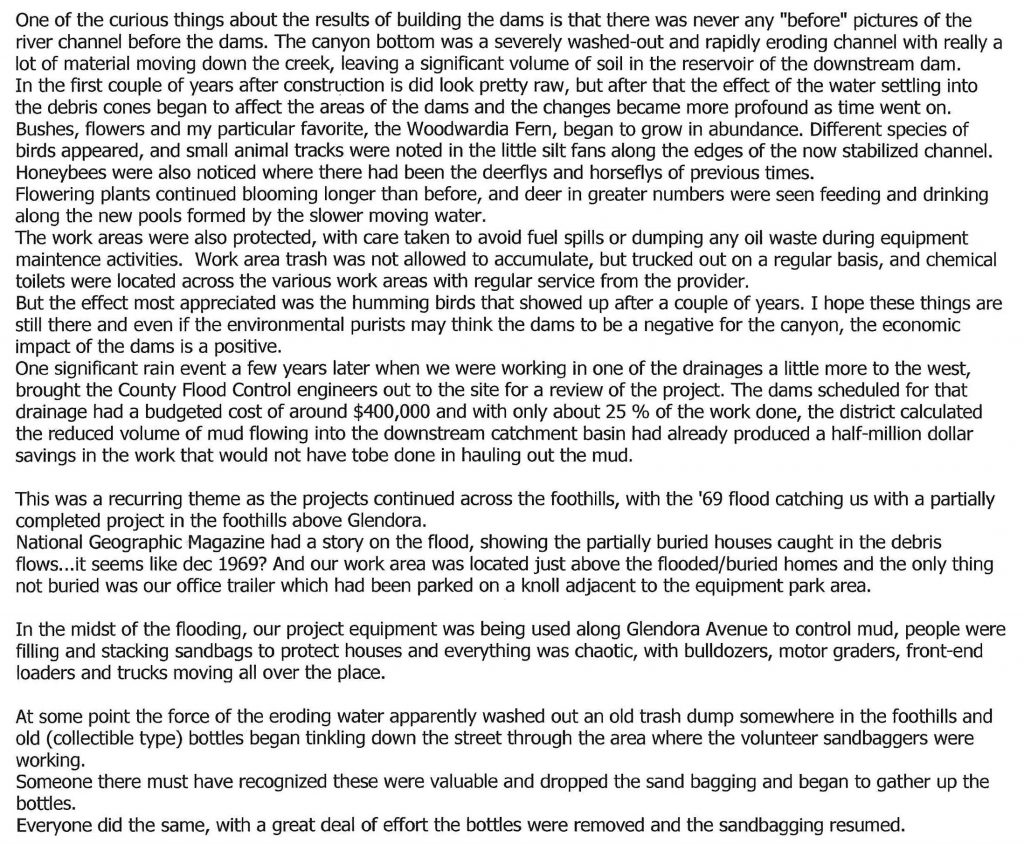

A tractor shovel begins trenching a site for a foundation of a check dam. This spot is located just downstream from Sturtevant Camp. Circa 1962

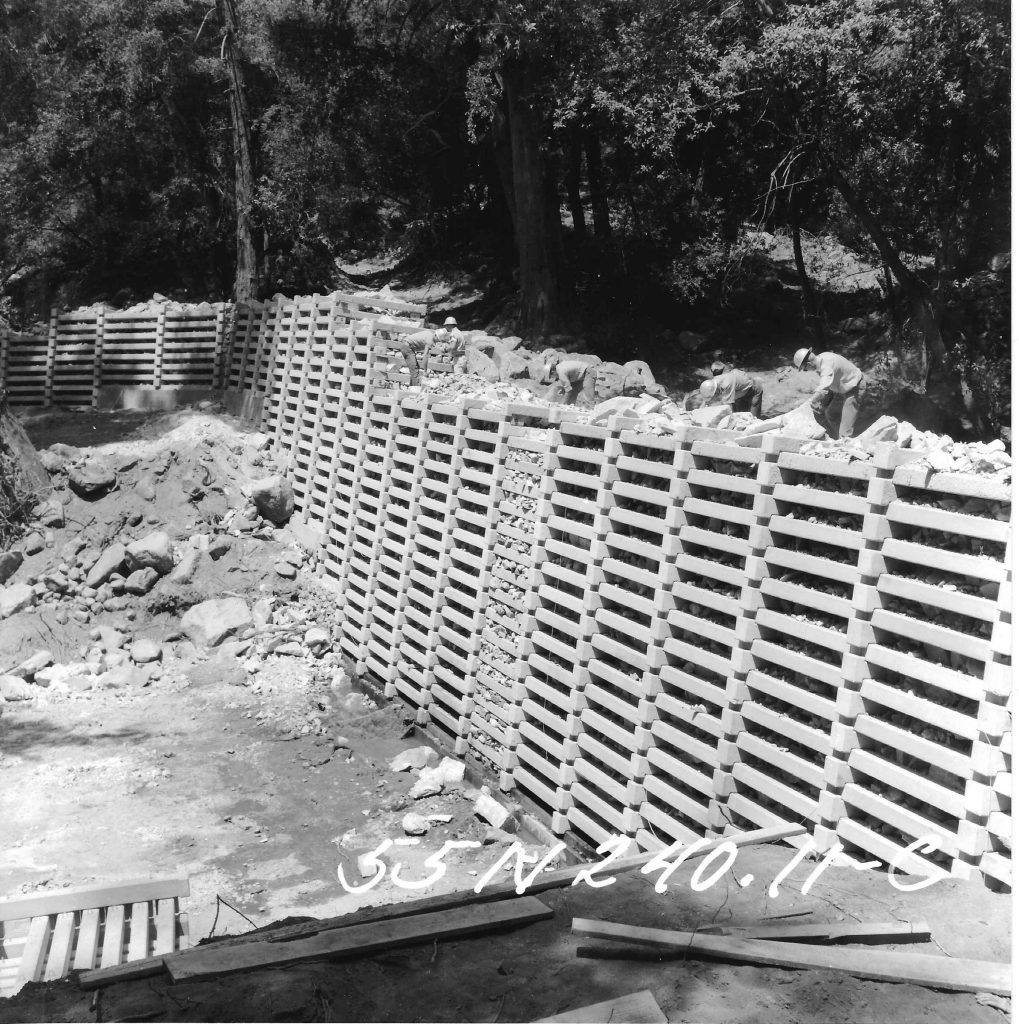

Here are some photos of the Chantry Flats check dams during their construction back in the early 1960′s. The U.S. Forest Service and Los Angeles County Flood Control District teamed up to engineer and construct these Lincoln Log type structures in many of the front country canyons of the Angeles National Forest. These structures were designed to keep the stream bed’s ever-moving alluvium “in check” with hopes of reducing the accumulation of sand and rock in the Big Santa Anita’s reservoir further down canyon. Regardless of how they’ve performed, they’re here to stay for the foreseeable future. The paved fire road that you begin your descent down into Robert’s Camp is the beginning of the construction road that was bull dozed all the way past Sturtevant Camp. Another road was also built on up the Winter Creek and beyond Hoegee’s trail camp. Today you can still make out the remnant switch backs of the “Burma Road” which climbed up and past Sturtevant Falls. Look for the non-native Italian cypress, pines and even eucalyptus trees that were planted on the abandoned road bed after the dams were installed. The Big Santa Anita Canyon Trails Map depicts the location of the abandoned Burma Road. The map is available at Adams Pack Station or canyoncartography.com Following the road is a hazardous proposition any time of year, so be especially careful for drop-offs, rattlesnakes, etc. If you’ve hiked on past Cascade picnic area, you’ll strain to imagine that a road ran through here, wide enough to accomodate cement mixers, skip loaders, cranes and more.

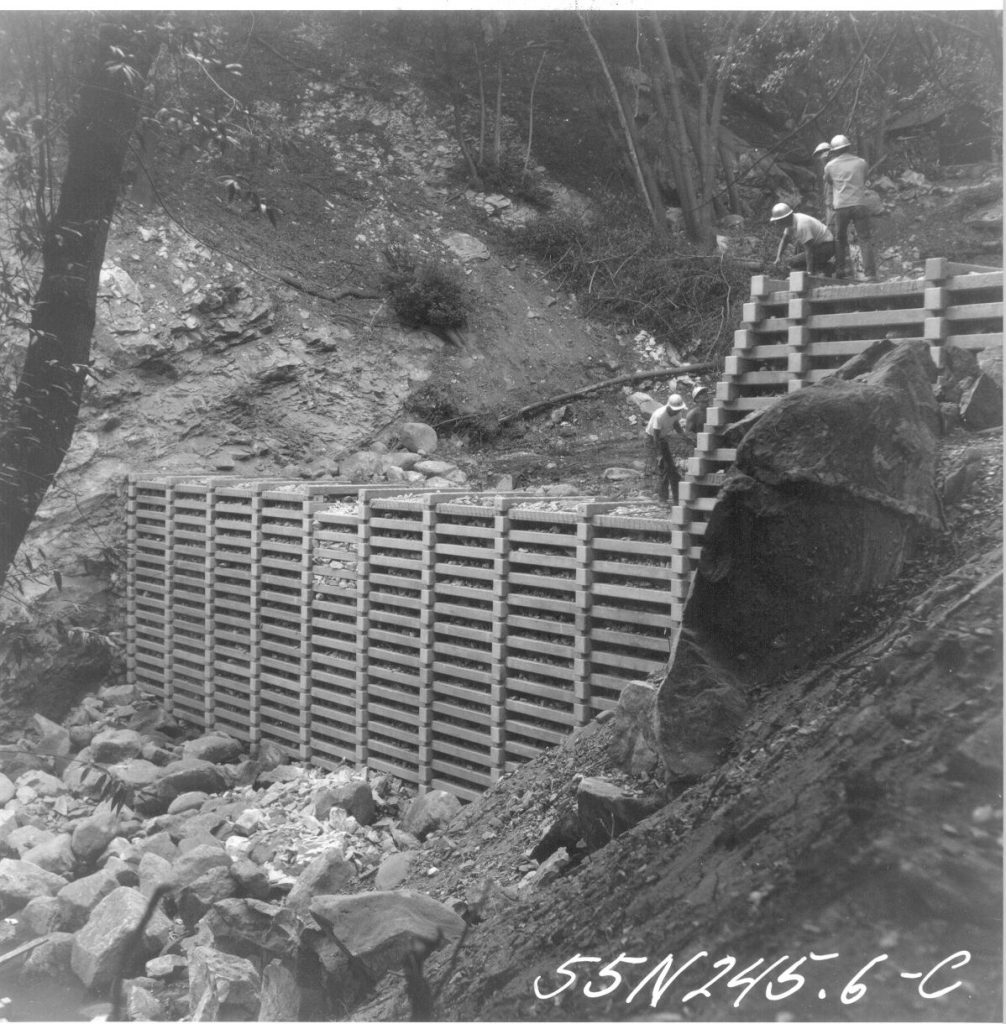

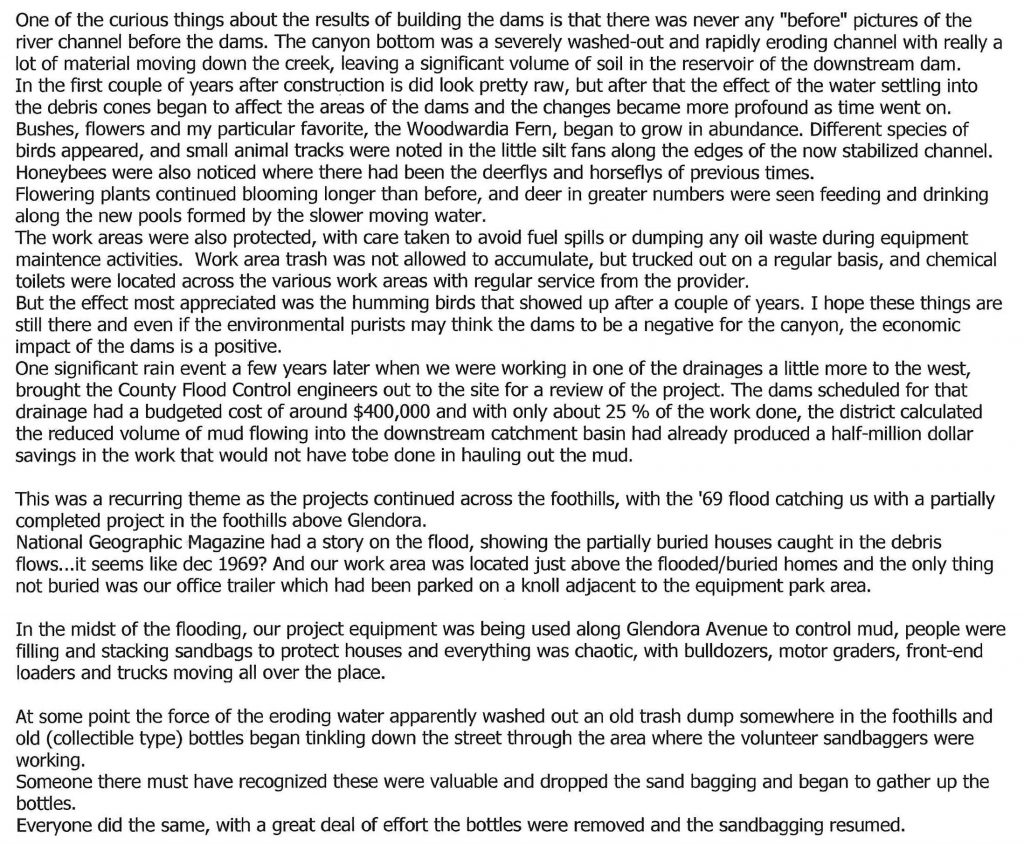

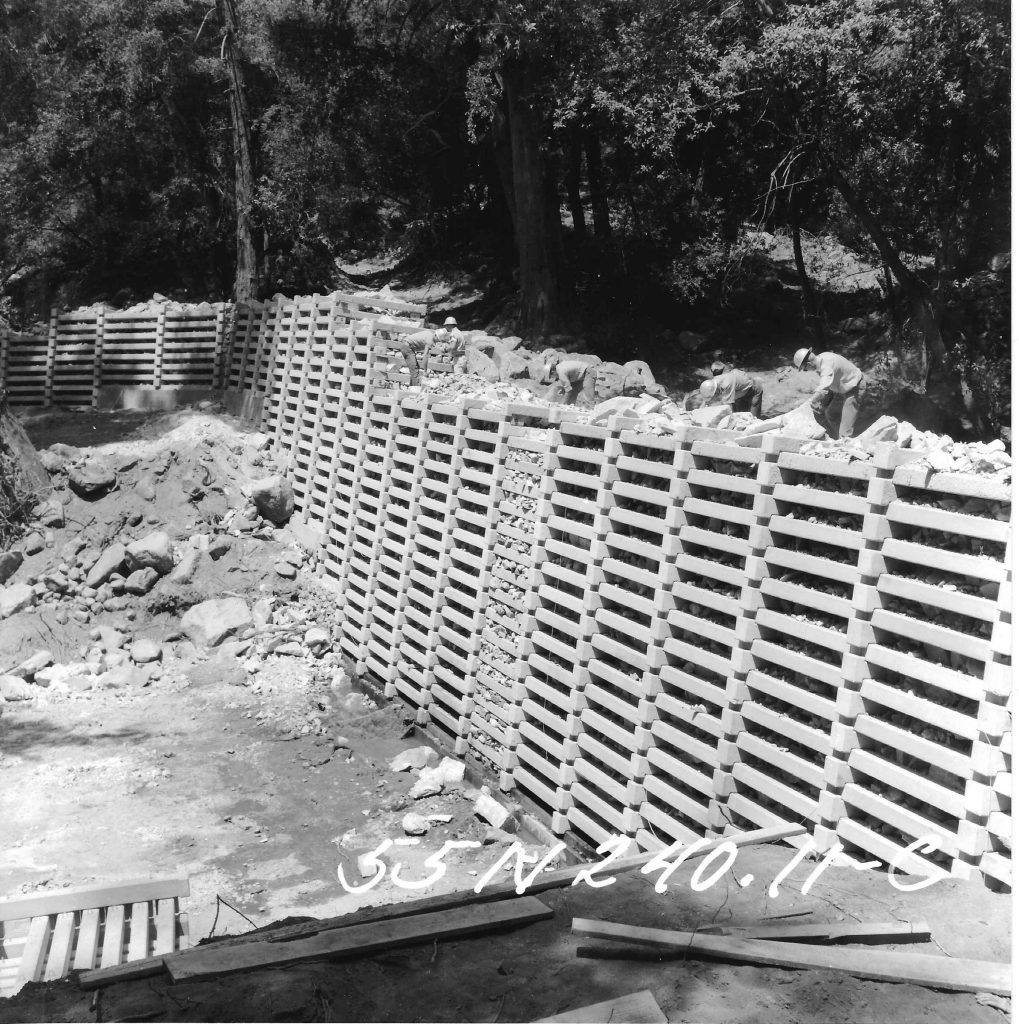

A check dam nears completion at Cascade Picnic Area, Big Santa Anita Canyon. A gunite cap will be added next. Circa 1963.

The destruction of pristine riparian environments would be unthinkable in our day and age. Yet, during the late 1950′s, this type of project was considered prudent land management and protection of watersheds. Essentially, the dams have changed the natural hydraulic grade of much of the Big Santa Anita Canyon and Winter Creek. The dams have created a stair-step type of profile in sections of the canyon bottom. Behind each dam are thousands of cubic yards of alluvium (sand, gravels and boulders) that are for now “stuck” in a static location. One day nature will have her way and there will be a phenomenal movement of material that will wash downstream. The engineers referred to this material behind each dam as a “debris cone.” In 1969, an El Nino storm pattern brought torrential rainfall to Southern California. One night during the ’69 Flood, a number of the smaller “sill dams” blew out. A sill dam is the lower (smaller) dam that you’ll often see just below or downstream of the larger check dam. The sill dam’s function is to protect the foundation of the larger check dam. Anywhere upstream of Cascade picnic area, you’ll notice that all the check dams have their accompanying sill dams. Anywhere below the confluence of the North Fork, you’ll notice that these sill dams are missing. Look carefully and notice the exposed foundations of the dams. One day they may collapse. This all happened during one set of storms in ’69! Slowly, nature has been healing from all this damming of the canyon. Decades later you can see the ivy, black berry bushes, mosses, fallen trees and sharp-edged boulders softening the scene. Canyon wrens flit back and forth into the aging rip-rap after spring floods ring through the canyons. Stout, black rattlesnakes gently drape their coils off the edge of the walls of the dams during the warm, drowsy days of August. The canyon is gradually claiming all the dams. We’re just hiking and feeling all this. in one part of this long, long timeline.

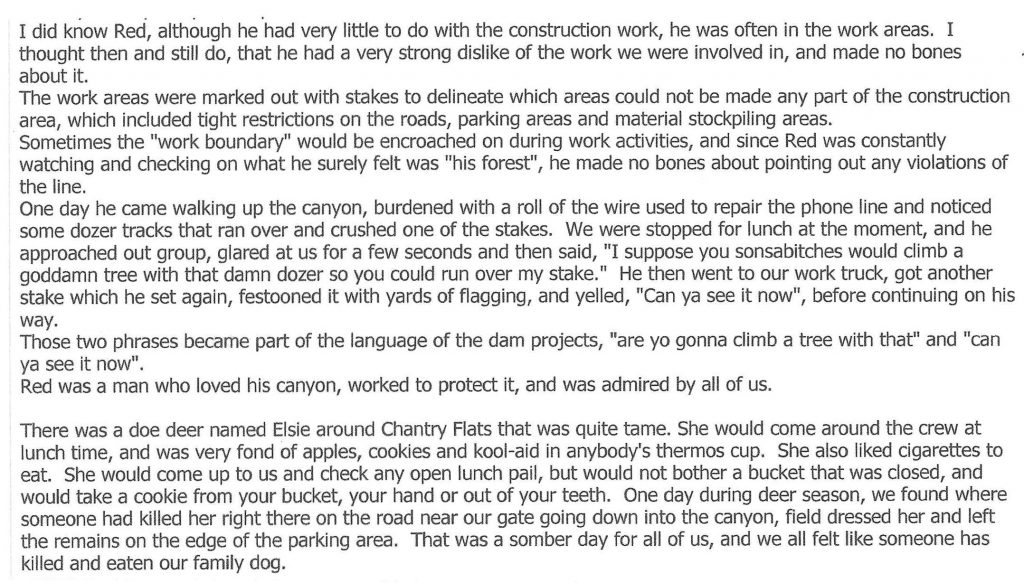

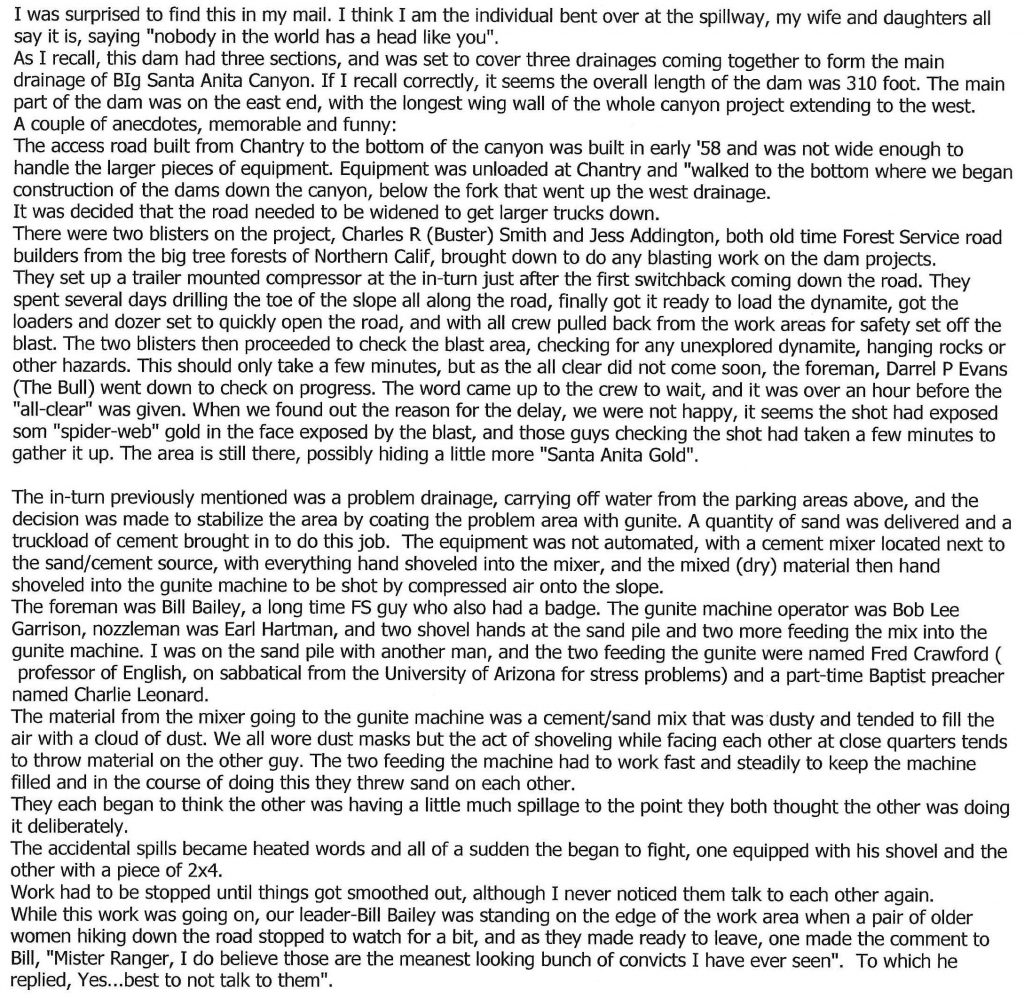

November, 2015. I recently heard from Dennis Logue, a member of the construction crew who built both the road and dams starting back in 1958. We began corresponding. He graciously has given permission for me to add his memories in the form of several letters to Canyon Cartography, describing the project and some of the colorful characters that were involved. Here they are:

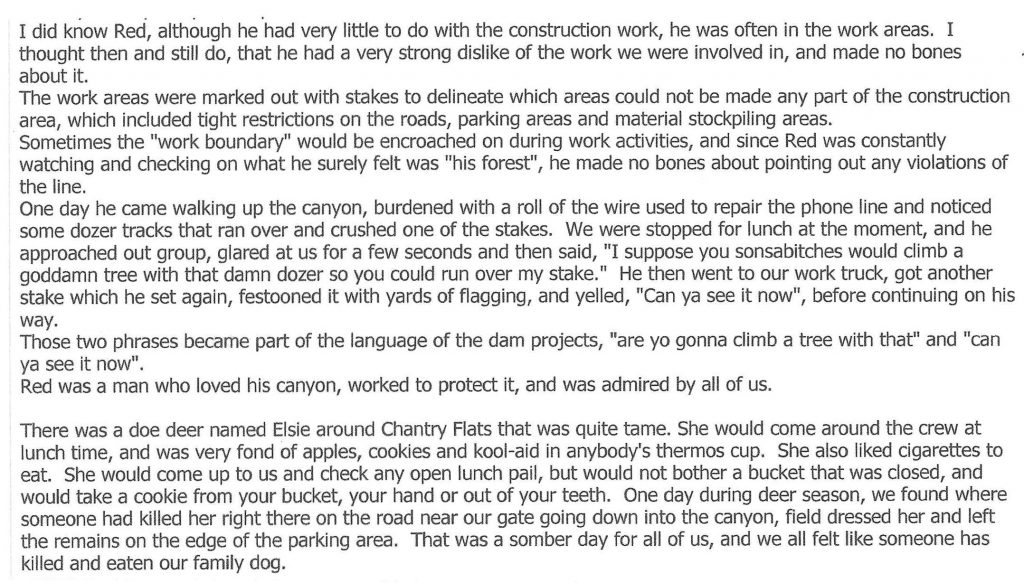

The first letter from Dennis. Red Shangraw & Elsie the deer

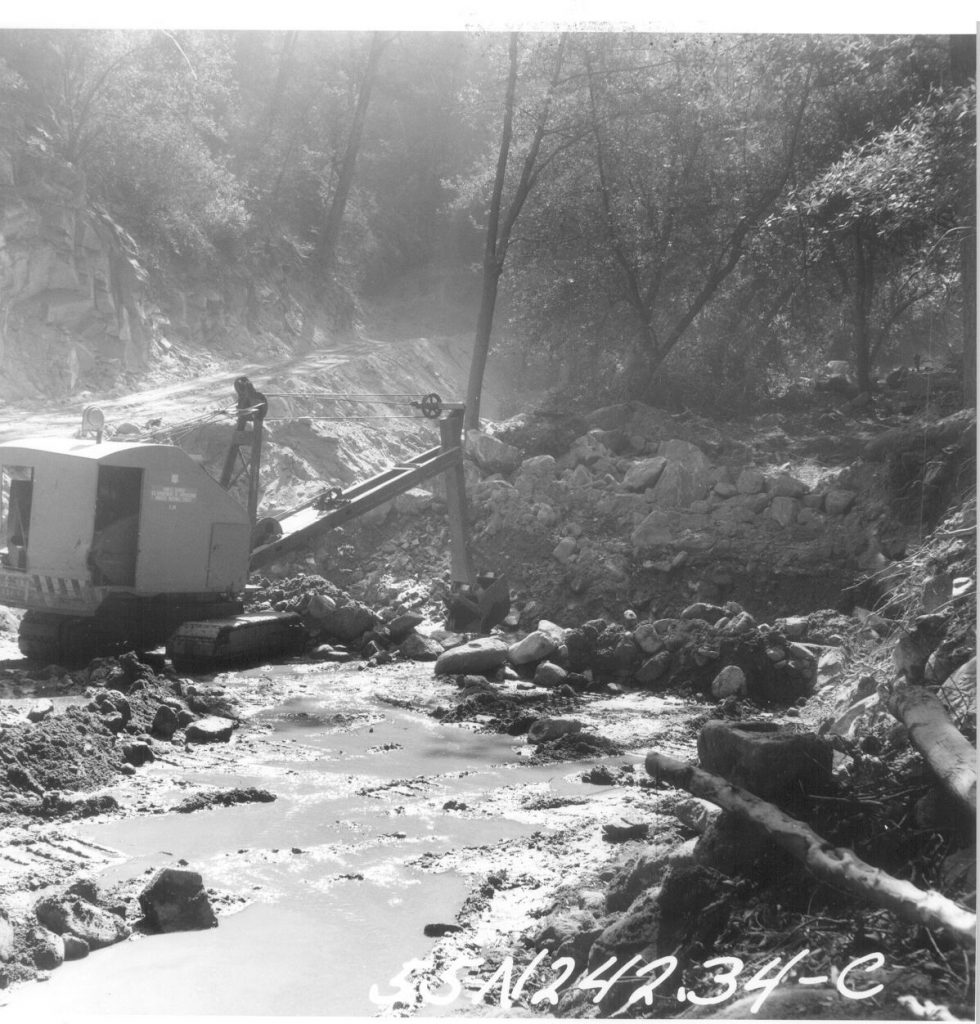

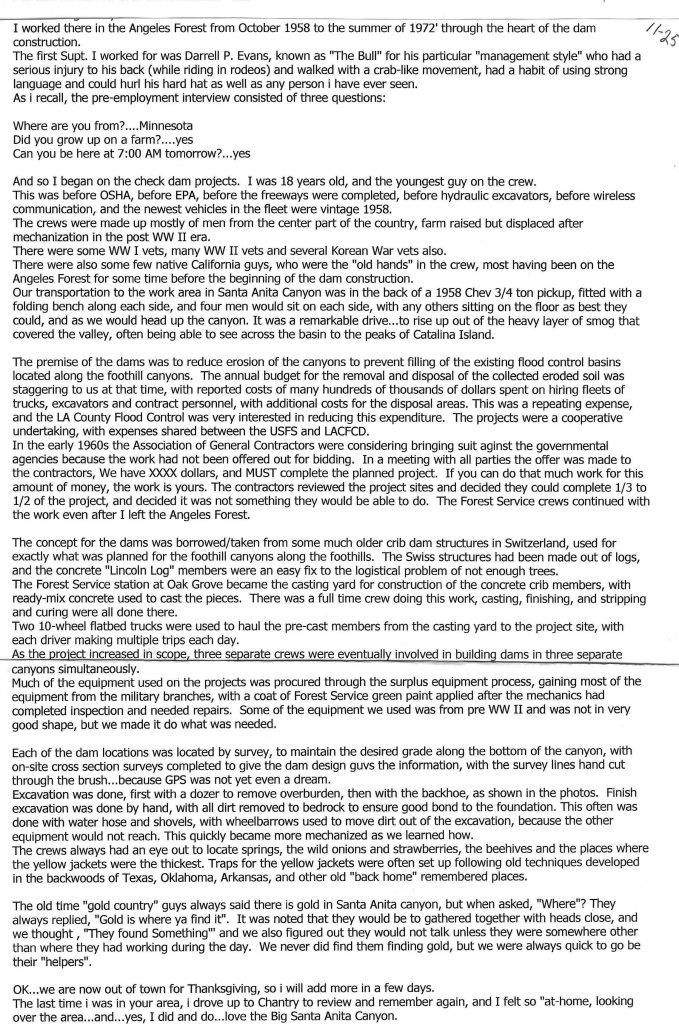

Dennis Logue is seen working on uppermost check dam in Big Santa Anita Canyon. July 1962. He’s the third man out to the left near the future spillway.

Second letter describing challenge of road building and method of applying gunite.

Third letter describing return of riparian plants and local animals. Response to 1969 Flood.

Fourth letter covering Dennis’ experience working with the crew on dams along with details on excavating for check dams.